How to play the patriotic card and win by a landslide

A strong prime minister given to bellicose rhetoric looking to increase her majority. Remind you of anyone?

When the Prime Minister announced the election, I condemned her for going to the country early to take advantage of her opinion-poll lead. It was a cynical attempt to exploit Labour’s troubles and to increase her majority before the opposition could replace its unpopular leader, I said. She was worried the economy was going to take a turn for the worse, I commented, thinking I was making a clever point.

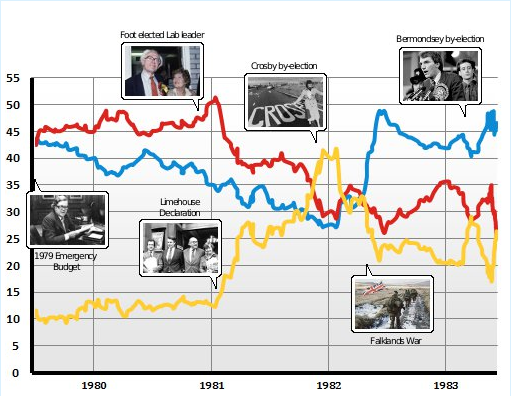

But I had no idea that Michael Foot was going to lose quite so badly. For her first two years in No 10, Margaret Thatcher was deeply unpopular. Unemployment had risen from one million – “Labour Isn’t Working” – to four million, and her policy of monetarism didn’t seem to be working either. I realised that Labour was not in a good state: many of the party’s right wing had broken away to form the Social Democratic Party, which, in alliance with the Liberals, was riding at 40 per cent in the opinion polls at the end of 1981, with Labour in second place on 30 per cent and the Conservatives on 27 per cent.

But the SDP bubble deflated and then came the Falklands War. Thatcher’s popularity soared, and it was the support for the SDP-Liberal Alliance that collapsed. After a dip, Labour seemed to be gaining ground. What I hadn’t realised was that the economic recovery was feeding into political support that kept Thatcher’s stock high.

The 1983 election was my first as a journalist. I was a reporter at the New Statesman, shrilly critical of Thatcher’s conduct of the Falklands War and puritanically disapproving of the wave of jingoism that swept the country, even though I agreed with Foot that the aggression of the Argentinian dictatorship must be resisted.

I thought Foot was a great man, although he was embarrassingly old, and old-fashioned, and the Labour Party organisation was hopeless. But at least the party had seen off Tony Benn’s challenge for the deputy leadership, defeated by my hero Denis Healey, who might have been a right-winger, a dirty word in Labour circles then as now, but he was a proper leader.

Part of me must have known Labour was heading for disaster – otherwise I would not have accused Thatcher of timing the election for her advantage. But I remember listening to the results on a radio at the count of my MP, Peter Shore, soon to be the fourth-placed candidate in the Labour leadership election, and being surprised and disappointed by the Tory landslide.

The parallels between then and now would be implausible if a novelist attempted them. The last time the Conservatives in government had a 21-point lead in the opinion polls was on the day before election day in 1983. Jeremy Corbyn is mobbed for selfies by enthusiastic supporters wherever he goes, just as Foot spoke to enthusiastic crowds of the Labour faithful. Joyce Gould, Labour’s national organiser, wrote in her memoir that “these meetings were interpreted as us doing well”, but her view was that they were “Labour supporters gathering together for warmth”. And then this week Theresa May’s declaration of war against Brussels was such an echo of the Falklands factor that it felt as if a task force was being assembled.

Of course, there are differences too, but they are not in Labour’s favour. Foot became leader as a compromise between right and left, but he was firmly opposed to Benn and the fightback against the so-called hard left began under him – even if the Bennites dictated most of the policies. Corbyn, on the other hand, represents that old Leninist tradition, a strand that has always existed in the party but which has never led it. This time, they have the leadership even if they don’t control most of the policies.

Today’s Lib Dem resurgence is also rather different from the excitement of a new party then. The SDP-Liberal Alliance won almost as many votes as Labour – 26 per cent to 28 per cent – but ended up with just 23 seats, which is roughly what Tim Farron can hope for this time. This time, the Lib Dems have a clear position on Brexit that allows them to take votes from Labour, but which gives them little purchase on the Tories.

And it is Brexit – Theresa May’s Falklands – that is the big difference as well as the big similarity between my first election as a journalist and my ninth. Many Labour supporters find the Prime Minister’s bellicose patriotism embarrassing, but their views are shared by a small minority of the electorate. Most voters, and I would guess even most people who voted to remain in the EU, think that EU leaders are pushing their luck and cheer May for standing up to them. The Falklands War created the image of Thatcher as a strong and resolute leader – even though the war happened only because the Argentinian junta misread the signals she sent. Brexit is doing the same for May, even though she was a Remainer.

The way the story ended 34 years ago was with a Conservative majority of 144 seats, and my part in it ended with my becoming – in the small hours of the morning on 10 June on Cambridge Heath Road in Bethnal Green – a dedicated Labour pragmatist, committed to whatever it took to win.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies