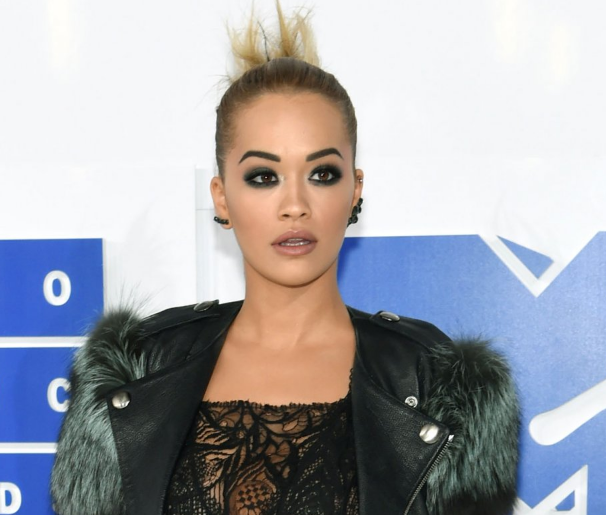

If you think freezing your eggs in your twenties like Rita Ora is a good idea, you need to read this

Yesterday evening for the first time there were several women in their mid-twenties at the free ‘Fertility Options’ seminar I was presenting. I wish they knew the truth

Last week, 26-year-old singer Rita Ora made headlines when she revealed on an Australian television show that she had frozen her eggs in her early twenties. Her doctor had apparently recommended the procedure, as she’d always wanted a big family. In Ora’s words: “He said, ‘You’re healthy now and it would be great; why not put them away and then you never have to worry about it again?’”

This prompted thousands of perfectly healthy 20-somethings to ask themselves whether they too should be thinking about freezing their eggs. Indeed, yesterday evening for the first time there were several women in their mid-twenties at the free “Fertility Options” seminar I present at the London Women’s Clinic – a testament, it seems, to the influence of media stories on this subject.

But here is the problem: media stories rarely provide the full context. although I happen to think egg freezing can be a very useful technology for some women, it is simply irresponsible to suggest – explicitly or implicitly – that women in their twenties consider it.

Over the past year, I have been working on a large-scale research project on egg freezing in the UK, speaking with hundreds of women who have frozen their eggs or who are thinking about doing so. Only one has been under 30. And there is a very good reason for this: eggs frozen in the UK for “social reasons” have a maximum storage limit of 10 years. This means that eggs that are unused within 10 years will be taken out of the cryopreservation tank and “allowed to perish”.

If a woman is not ready to use her eggs but does not wish to discard them, she can get around the law in one of two ways. Either she can export her eggs to a clinic overseas (where the 10-year storage limit does not apply), or she can thaw and fertilise her eggs to create embryos, and freeze the resulting embryos until she is ready to attempt conception.

Clearly, neither of these potential solutions is ideal, and much has already been written about the law imposing an “illogical” and counterproductive timeframe on women who have frozen their eggs. As Professor Emily Jackson says: “It seems likely that women faced with the imminent destruction of their eggs will feel under pressure to use their eggs before time runs out for them, ironically perhaps creating a newly ticking non-biological clock.”

Indeed, right now we are seeing the first cohort of women – the “social pioneers” who froze their eggs in 2007 and 2008 – grapple with such novel dilemmas, and we know from their experiences that making decisions about one’s frozen eggs can be both complicated and emotionally difficult.

Earlier this year, one woman who froze her eggs in 2007 as a 33-year-old applied to the HFEA for an extension of her storage period, which ends this month. The HFEA’s response was to note that, since the limit is due to Government legislation, they “don’t have the powers to make any changes”.

But it seems the Government has no plans to consider this issue either. MP Tonia Antoniazzi’s question to Parliament on 22 November, about the merits of replacing the 10-year statutory time limit with a system of five-yearly reviews, received the somewhat unsatisfactory answer from the Secretary of State for Health: “There are no current plans to review the provisions of these regulations.”

The fact that this parliamentary exchange passed without remark in the same week that Rita Ora made multiple headlines illustrates the myopia of our focus on fertility issues, and the potential for celebrity stories to mislead women.

None of last week’s coverage pointed out that Rita Ora, who reportedly froze her eggs aged 22, would have to use them by the time she is 32, effectively negating the potential advantages of freezing eggs as an “insurance policy” for later motherhood. Of course, it may be that in her case, there was an unreported underlying health condition which led to concerns about her fertility – and if eggs are frozen for medical reasons, they can be stored for up to 55 years.

It may be that Ora froze her eggs outside of the UK, perhaps in the US, where such a storage limit does not apply. Or it may be that she was simply given bad advice. We just don’t know. But one thing I do know is that her case should not be presented as an example to other young women, unnecessarily fuelling reproductive anxieties.

Don't get me wrong – I think it's great that younger women are thinking about their fertility, but these considerations must take place within a broader context if women are not to be left misguided.

Now 38, I was part of a generation for whom fertility education was exclusively focused on contraception. Concerned with avoiding the dangers of STDs and “accidental” pregnancies, our preoccupation was to make sex “safe”, and most of us didn’t even think to worry about our ovarian reserve until our fertility levels had already fallen off the proverbial cliff edge. So I enthusiastically welcome better fertility education and awareness for women. But the pendulum has swung too far in the opposite direction.

Women are bombarded with messages about fertility decline – the 35th birthday a dramatic death knell for fertility – in ways that both exaggerate the risks and portray reproduction as a matter solely of individual responsibility. Yes, we women must contend with our cruel biology. But we must also contend with workplaces that are unfriendly for families, house prices that are too high, and a dating scene that is not always conducive to “settling down and having babies”.

Egg freezing is only one part of the solution to the “problem” of later motherhood, and it is the part that most disproportionately places the physical, emotional, and economic costs on individual women’s shoulders. Moreover, if doctors and fertility specialists really think that women should consider freezing their eggs at younger ages, when they are likely to have better quality eggs, it is their responsibility to actively lobby for a parliamentary review of the ill-fitting 10-year storage limit.

Rita Ora’s decision may have been the right one for her, but suggesting – either explicitly or implicitly – that women in their early twenties consider freezing their eggs is not only irresponsible within the current regulatory framework, but also forms part of a broader neoliberal atmosphere that views reproductive decisions and actions as purely individual choices, rather than the socially embedded, complex deliberations most of us know them to be.

Dr Zeynep Gurtin is Senior Research Associate at the London Women’s Clinic and Visiting Researcher at the Centre for Family Research at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies