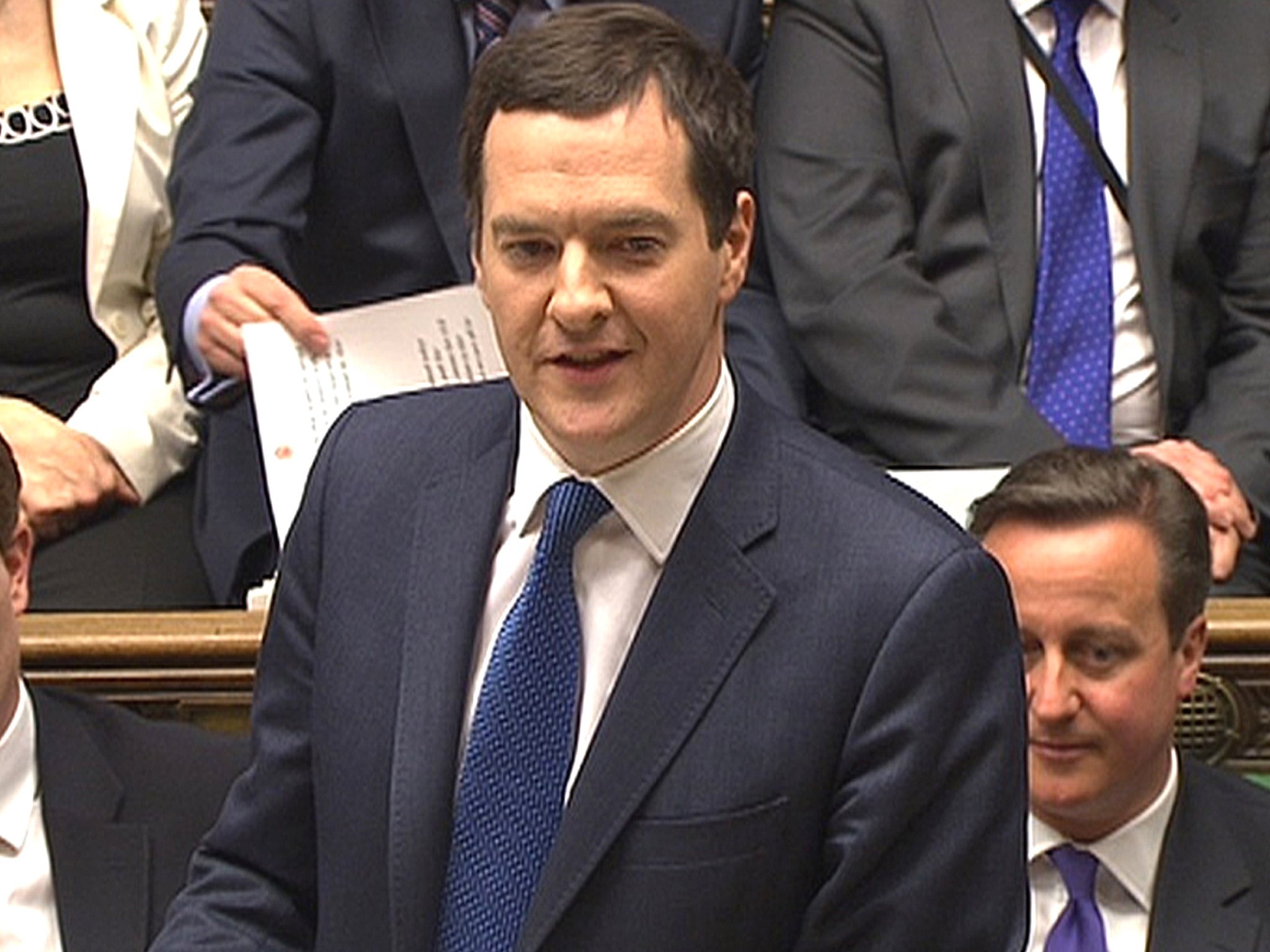

This Budget makes George Osborne the Bismarck of our time

Not since the 1870s has there been such a shift. From now on, we will be responsible for our own pensions

Every now and again a politician comes up with a big idea, one that either changes the way we live and work, or is a necessary and obvious response to changes that are already taking place in our society and which reinforces those changes.

There have been a handful of these. The most important of all came from Otto von Bismarck, who created the modern welfare state in Germany from the 1870s onwards. Counter-cyclical fiscal policy was developed in the United States under Franklin D Roosevelt in the 1930s as a response the Great Depression. More recent big ideas have been privatisation and independence for central banks.

The new big idea evolving here and given a huge boost by the Budget, is that individuals – not their employers – should be responsible for their pensions. Rationally this must make sense, given the changes in the labour market. People change their job many times. They may move to a different country when they retire. There may soon be more people self-employed than working for the state. The idea of a single national retirement age no longer reflects the way people behave. And we are living longer.

These shifts are creeping, incremental ones. Here and elsewhere pension policy is scrambling to catch up. So change is incremental too and you have to start from where you are. The state will continue to provide a minimum. No one will be destitute. Government employees will continue to get guaranteed pensions, though political pressure from the burden of these on taxpayers will rise. Company pensions will continue too, and the new requirements on employers will go some way to reverse the damage from two decades of policies that have been at best ill-advised and at worst downright hostile. But while the old system will continue in a patched-up way, for most people a comfortable retirement will require them to take some action.

Actually, we already know this. People nearing retirement age talk of their homes as their pension pot. The more astute (and affluent) have bought buy-to-let properties. (Is it true that one in three MPs owns a buy-to-let?) But to rely on UK property rather than a spread of investments is to make a punt on a single asset class. Besides, the country does rather need to invest in commerce and industry too.

What we have not had until now, though, are straightforward ways of building up wealth through saving in shares. The increase in the amount of money people can put into ISAs and the ending of the annuity trap go a long way towards correcting this. ISAs (Individual Savings Accounts) and their predecessor PEPs (Personal Equity Plans) have been a useful support for pension planning and there are stories of the first ISA millionaires coming through. In theory, anyone who put the maximum allowance into these, starting in 1986 and reinvesting all income, could have built up a pot of that order. Compound interest is a wonderful thing.

However it was the changes to pensions that caused the big shock last week. Rules about how much you can put aside for a personal pension, what you can do with the pot, and the tax treatment of that pot, have been chopped and changed almost every year. The one thing that anyone planning for retirement might reasonably expect from government is continuity of pension policy, and successive chancellors have failed to deliver it.

Some stupidities continue. The cap on the size of a pension pot, as opposed to a cap on the amount people can save for a pension, is a tax on investment performance. But the freedom to take money out when you want to and the freedom not to have to buy an annuity together are game-changers. A huge disincentive has been removed. Annuities are not compulsory under the present system but in practice most people have been pushed towards them, and, as the Chancellor acknowledged, rates have been dreadful.

So, is this a practical response to a changing world, or something bigger? Will we nudge society away from Bismarck's German vision of 140 years ago, and towards the self-help, friendly society, co-operative traditions of 19th-century Britain?

I think it will turn out to be both. It is common sense that the more fluid the labour market the more important it is that the pension should be attached to the person not the job. But the bigger story is about trust. We can't trust companies for our pensions. Some companies are great, others will disappear. We can't trust governments either. Who knows the complexion of a government in 20 or 30 years' time? We have to trust ourselves. That means trusting our own judgement to be sensible about how much we spend and save, and how best to ensure that we have a secure income in retirement.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies