Take note, Ed Miliband: Starting a fight doesn’t make you strong

I cannot understand how inciting fury is in itself an act of good leadership

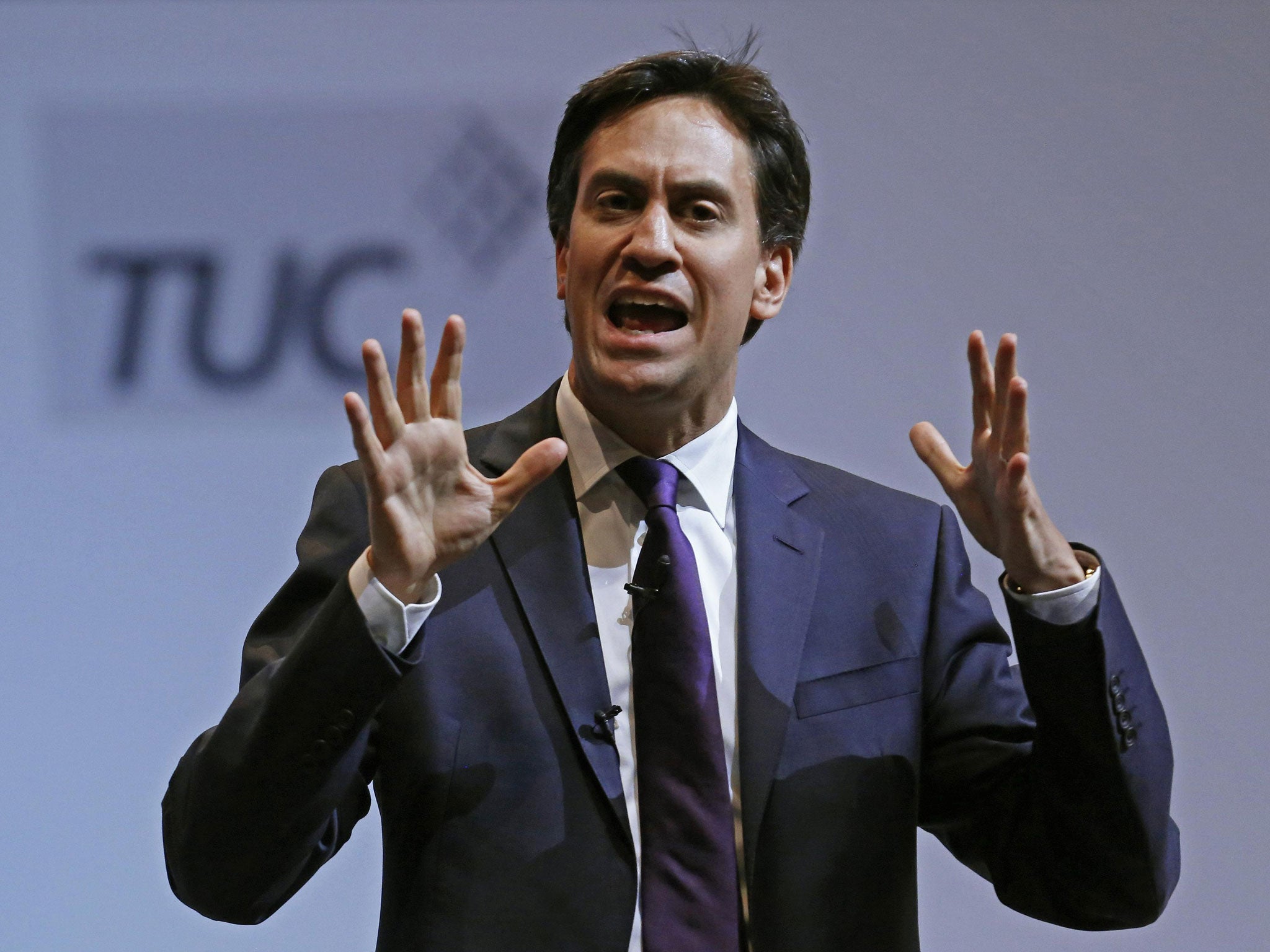

The fashionable definition of strong leadership takes an eccentric and limited form. A party leader is deemed mighty if he or she “takes on” their party in an equivalent of a shoot-out at the OK Corral. A party leader who fails to do so is dismissed as weak. This week it is Ed Miliband’s turn to be judged on these terms. His visit to the TUC annual conference was billed in advance as the ultimate test of his leadership. He was expected to provoke howls of disapproval in the normally sleepy town of Bournemouth where trade unionists had gathered. When the howls did not materialise and Miliband delivered a dull speech, he was widely derided.

I do not defend the speech, which was not very good. Miliband should have explained more fully what he was seeking to achieve in changing his party’s relationship with the unions and how that fitted into his plans for the country. Personally, I have never understood, beyond the obvious need for cash on Labour’s side, why the link has endured in this form for so long. Potential candidates seeking a seat are asked within seconds whether they know the regional officer of Unite or the GMB. If they do not they are often doomed. This is not a sensible way of electing an effective parliamentary party.

Conversely it is not easy to discern what unions get out of the link either. As Donald Macintyre pointed out on these pages on Tuesday, many unions are not affiliated to Labour and do not seem to suffer from the lack of formal association. Those that are tend to be kept at a distance because the leadership is partly embarrassed at the link. Indeed, Tony Blair turned looking embarrassed when he spoke at the TUC conference into an art form, conveying to the wider electorate, without saying as much, that he would rather be anywhere else in the world.

I cannot remember a single word of a speech Blair uttered at a TUC conference and he was capable of delivering mesmerising addresses. Come to think of it, I cannot recall a single speech from a leader at a TUC conference since Jim Callaghan famously hinted that he would not be calling a general election in 1978. Even then his hint only acquired significance retrospectively. No one had a clue what he was going on about when he sang a verse or two from a song attributed to Marie Lloyd.

In the 1990s, I presented live television coverage at the TUC conference. Each year we billed the Labour leader’s speech as the equivalent of a fragile figure entering a lion’s den. Each time there was no roar, not even a whimper. There was nothing much at all. Miliband was part of a long tradition. Presumably leaders are saving themselves for their much bigger party conference speech that follows.

It would not have done Miliband much good if he had provoked a violent roar in Bournemouth. A moment’s apparent heroism soon leads to stories of splits. If Miliband retreats on his plans for internal reform he will deserve derision. But I cannot understand how inciting internal fury is in itself an act of impressive leadership.

It never used to be the main criteria. Part of a much wider test used to be the degree to which leaders could keep their unruly parties united. Perhaps Margaret Thatcher started the new fashion when she openly “took on” the so- called wets in her government. But she moved with her party most of the time. There were no titanic confrontations until her removal at the end, the biggest insurrection of the lot.

Neil Kinnock was a closer model, having no choice but to challenge a party that had been slaughtered at the 1983 election. But as he discovered, it continued to be slaughtered – partly because voters saw little other than a leader at loggerheads with his party. Blair famously sought definition against Labour, but I am not sure that the distinctiveness was what made him so popular early on. His weak party more or less accepted everything he did or said. There were no great battles in public, only a private one of epic proportions with Gordon Brown. Blair’s message might have been “It’s safe to vote for me because I am distant from my party” and his party would have cheered rapturously.

In opposition David Cameron occasionally asked allies for ideas that would challenge his party. But if he got the ideas he rarely followed up on them. Rather cleverly, Cameron gave the impression of taking on the rank and file without actually doing so. He was so effective that some members felt challenged when they had not been.

Only Nick Clegg seems outside the pattern. Indeed, in his case the media tends to reverse the question: Why have the Liberal Democrats not taken on Nick Clegg? No doubt we shall all head for Glasgow at the weekend, where the Lib Dems gather for their conference, hoping to find mutinous activists. I expect a largely fruitless search.

Parties are weak, puny beasts these days. It is the easiest act of leadership to be seen taking them on. Sometimes a leader has no choice. But on the whole, it is probably better for any leader of any party to avoid prolonged noisy civil war. Internal fury is not always a sign of strong leadership.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies