A super sewer is a long overdue solution to London’s dirty secret

The costs are high, but the benefits will be great

In the normal course of events one does not often find oneself writing about sewers, but news of a certain sewer calls for comment. This is no ordinary sewer. It has sometimes been referred to as the “super sewer”. You might even call it the “hyper sewer”. Think not so much a pipe, more the Channel Tunnel. It will cost more than £4bn. And it is going to be built underneath London.

It is a 15-mile long solution to the worst pollution problem in the capital: the fact that these days, every time it rains, more or less, the 150-year-old Victorian drainage system discharges torrents of raw sewage directly into the River Thames, frequently killing large numbers of fish and other aquatic life, threatening public health, and despoiling the country’s premier watercourse.

This state of affairs is sometimes known as “London’s dirty secret”, and it is the last obstacle, and a formidable one, to the clean-up of the Thames which has been going on since 1964, when the official discharge of untreated raw sewage into the river came to an end.

It is popularly supposed that this had happened with the famous London sewer network built by the Victorian engineer Joseph Bazalgette in the 1860s, but what Bazalgette’s system actually did was collect all the sewage in the capital – itself a notable feat – and then shift it past the city centre, to be discharged downstream, still in its raw state. Although this was a substantial improvement on what had gone before, much of the filth still flowed back upriver on the tide, and the Thames long continued as a lifeless ditch –a detailed survey in 1957 found that there were no fish whatsoever in the river between Kew to the west of London, and Gravesend to the east.

It was only in 1964 that treatment works were installed at the downstream sewage outflows at Beckton and Crossness, and a real improvement began: fish quickly began to return, a process that was crowned in November 1974 with the arrival of the first Thames salmon for well over a century.

Since then, the improvement has continued; but it has been punctured with increasing frequency in recent years by discharges from 36 “combined sewage overflows” or CSOs, which let huge amounts of the bad stuff directly into the Thames when rainwater builds up in the drainage system; no less than 55m tonnes of it flowed into the river last year. (If they didn’t let it out into the river, it would back up into people’s loos).

It happens because there is more rainwater in the system than ever there was when Bazalgette built his drains, since much more of the ground is now covered in concrete and the water runs straight off it; and there is much more sewage, as London’s population in the 1860s was three million, and now it is closer to ten.

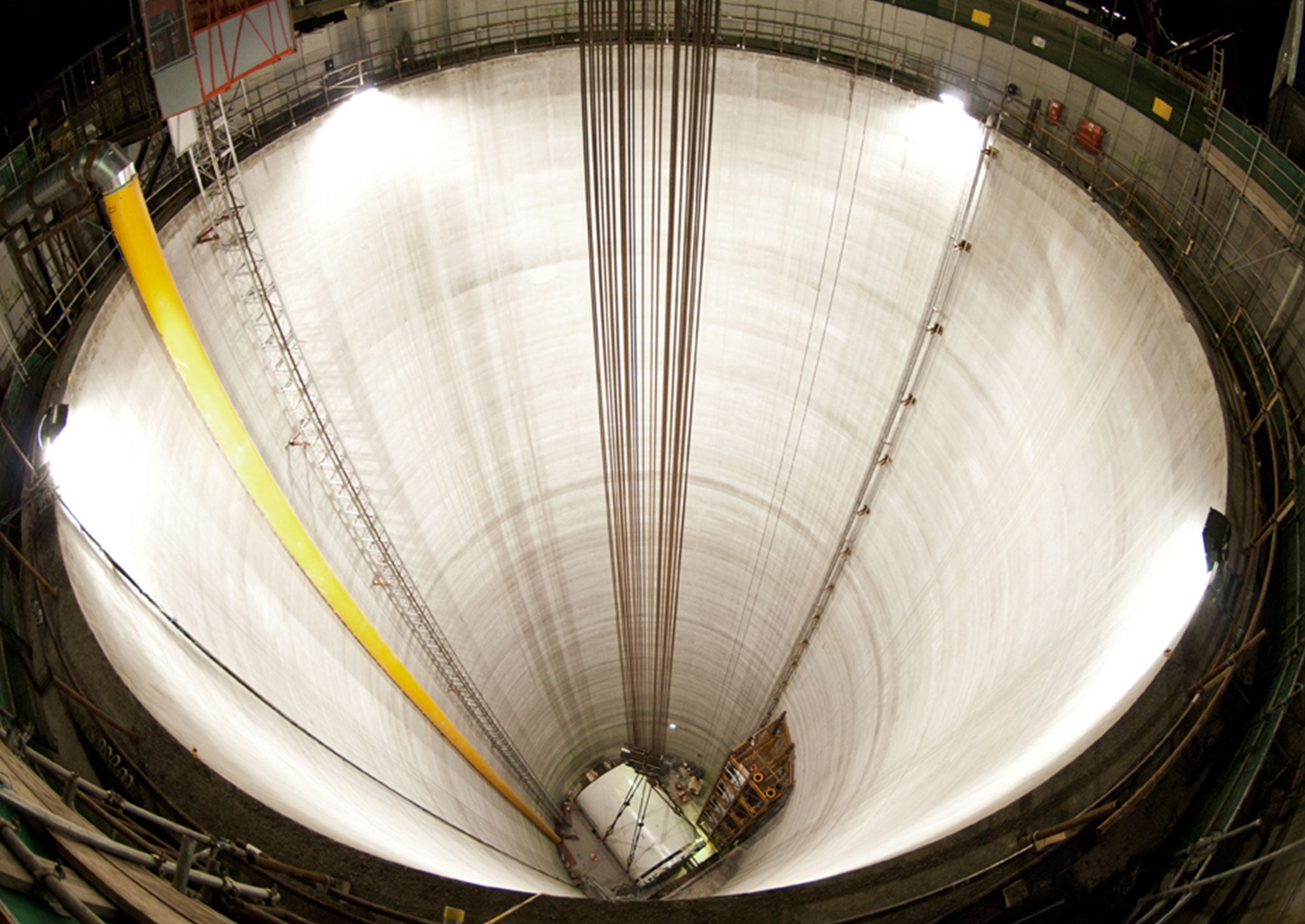

The proposed solution is the super sewer – its official name is the Thames Tideway Tunnel – which will intercept the rainstorm discharges from the CSOs and carry them, at between 100ft and 200ft below ground, across the capital to Abbey Mills in the East End, where the waste water will be treated before being returned to the river. After years of planning and discussion, not to say argument, the mammoth project was finally given the go-ahead by the Government last Friday. Construction will start in 2016, and will last seven years.

There will be substantial costs, economic and social, in the building of the super sewer by Thames Water: water bills for the company’s customers, like myself, will shoot up by £80 a year, and there will unfortunately be major disruption for residents living near the main tunnelling access sites, some of whom intend to challenge the decision to go ahead.

But a number of environmental groups warmly welcomed it last week and as someone who lives near the Thames, and loves the river, I feel it is absolutely essential. The discharges from the CSOs are vile and insupportable in the premier river of a country which claims its rivers in general are cleaner than they have been for more than a century. And they may well have been one of the reasons why the 30-year, multi-million pound project to restore salmon to the Thames as a breeding species has, alas, been a failure.

Joseph Balzagette’s masterpiece of sanitary engineering was a wonder in its day, but now it is springing leaks on a weekly basis. London’s dirty secret needs to be tackled.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies