Tom Sutcliffe: When art can't be taken at face value

The week in culture

Our predictability as animals is often an under-considered part of the artistic experience. By which I mean that we tend to assume that most of our fine-art experiences are a question of nurture rather than nature. They take place in the realm of the acquired, the rational and the carefully learnt, the presumption goes, so that what you feel in a gallery overlaps in a lot of ways with what you know – about art in general and this artist in particular. It's one reason why galleries stick up informative notices and most visitors find it impossible to resist them – because we believe, at some level, that looking in an art gallery is a form of scholarship. The erudite eye will see more clearly than the unlettered one.

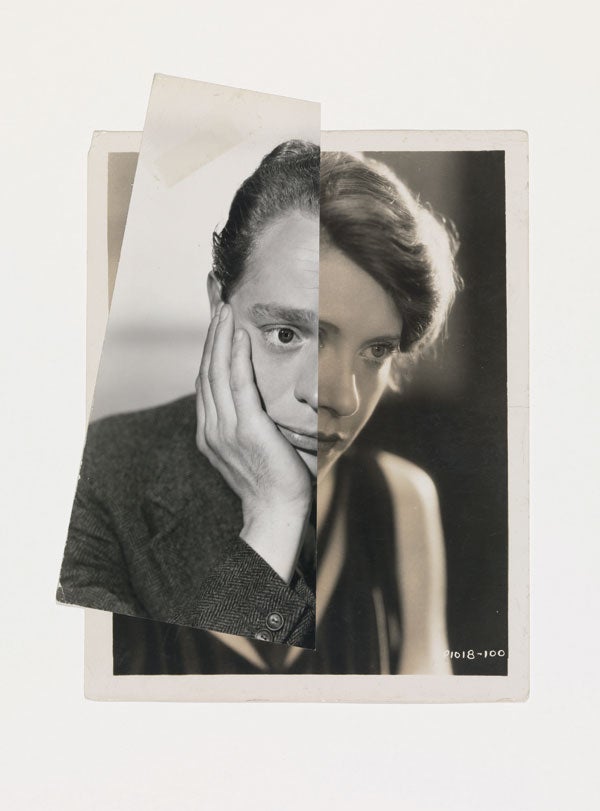

So it's interesting to encounter work which, though it could certainly be placed on a standard map of allusions and art history "isms", also seems to work directly on our most primal instincts. Walking round Whitechapel Art Gallery's show of the work of John Stezaker, you're constantly arrested by an odd disquiet, a feeling that your gut is still trying to work out something that your brain has already neatly categorised and has filed away.

Stezaker is a collagist – not a messy accumulative one like Kurt Schwitters or other early 20th-century exponents of the form, but a very neat and minimalist one. He uses found materials, most often vintage tourist postcards and film publicity stills, and, in many cases, Stezaker's work will feature only one clean-cut line or very simple assemblies, such as one rectangular image sitting with perfect symmetry within another. The messy bit, as in quite a lot of the more interesting art, lies on our side of the equation, because Stezaker takes advantage of two powerful adaptive instincts to generate something rich and strange out of the simplest conjunctions.

The first is our hard-wired appetite for the human face, which we will happily deploy on foliage, irregularly scorched bits of toast, and cloud masses, and which can be teased into operation with the most vestigial clues. A bit of hairline and collar will do it, as Stezaker demonstrates in a sequence of pictures titled Pair, in which publicity stills of minor Hollywood stars are overlaid with a scenic postcard, selected and aligned in such a way that one seems to bleed into the other. A mass of rocks or tree branches occupies the space where we would expect the facial features to be and so we enlist whatever is available to fill out our expectations. A horizontal cleft in the rock becomes an eye; a deep chasm between two cliffs is refigured as a loving or a hostile gaze. Our most urgent appetite with regard to faces, namely to interpret their expressions, is thwarted. Should this be read as "stonily implacable" or "durably unchanging"? At one level it's a bad pun – rock faces, geddit? At another it's a creative thwarting of our deep-rooted instinct to make sense of what we're looking at.

And that, in a larger sense, is the other appetite, the inner conviction that an image should be coherent, that what brings the two elements of a picture must be something more than the collagist's glue-pot. In a work called Insert Stezaker obscures the centre of a film-still that shows a woman confronting a man over an old-fashioned office-desk. Instead of the central detail that might help us to interpret the scene, we're given a hand-tinted Edwardian postcard of waves breaking over the front at Eastbourne. And – you are effectively powerless to prevent this reading from arising – you find yourself thinking of him as solid and resistant, and her as a surging, attacking, force.

Pull away for a moment and the indifference of each image to the other reasserts itself. They have nothing in common. Succumb again to the whole and you feel the tidal suck of the desire that this should tell one consistent story, not be a forced marriage of incompatibles. There's absolutely no mystery about what the images show, or how they've been constructed (Stezaker's geometry feels like the magician showing there's nothing up his sleeve) only a nagging sense that you might have misread the information somehow. And it's the animal in us that's feeling uneasy.

A chance to take an even closer look at Venus

I don't know whether you've ever really gazed at the navel of Botticelli's The Birth of Venus in the Uffizi, but it's an intriguing object seen up close. Not quite an "outie" it still presents a little protuberant bump, beneath an eyebrow-like dash of horizontal shadow. At the bottom a darker flick of paint gives the "button" itself its distinctive concavity. And, intriguingly, when you look really closely you can just see the faint grey outline of the underdrawing, offset a little to the south-west, as it were. Lean in to look at the little finger, with a magnifying glass, and you can see something similar has happened there, too. At which point, if you were actually in the Uffizi, a guard would probably dash forward and tackle you because you'd have to have stepped over the guard rail to get close enough. On Google Art Project, on the other hand, there's no problem because a seven-billion pixel digitised image of the painting allows you to mouse-click in to a startling degree of definition. Each of the 17 great world galleries have picked a work to be rendered at the same detail (in the Rijksmuseum it's Rembrandt's Night Watch) and you can also wander around the galleries with a kind of interior version of Google Street View. Whenever you spot a plus sign on a picture you can click on it to enlarge. The terrifying time-sponge of the internet has just added aesthetic pretensions to its powers of absorption.

Politics and literature on trial

Nick Clegg assures us that he hasn't been clocking off at 3pm, as some ill-informed reports had suggested, but dutifully sits up until the small hours poring over briefing papers. I'm not sure I'm reassured by this. In fact, you do sometimes fantasise that a impish Permanent Secretary might one day creep in and substitute Kakfa's Metamorphosis for the usual Whitehall bumf – complete with a Post-it note reading "You might find this has some relevance to your current situation". Alan Bennett explored a similar idea in his short story "The Uncommon Reader", in which the Queen, to the consternation of her ministers, became addicted to literature.

And in Canada the author Yann Martel actually tried to put it into practice, sending the Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper a book every two weeks, in the hope of broadening his horizons. Martel has just surrendered the fight, after 100 books, having received no acknowledgement but for the occasional pro-forma letter from Harper's staff. Politicians worry all the time about their economic literacy, but appear almost proud of their cultural illiteracy. But is it fanciful to suggest that if Hosni Mubarak had taken the time to read a few contemporary Egyptian novels he might have been less arrogantly detached from the people he ruled?

t.sutcliffe@independent.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies