David Lister: Call something a classic often enough and it becomes one

The Week in Arts

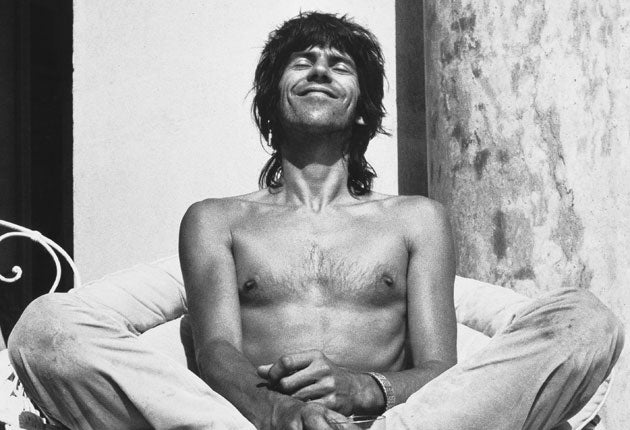

The Rolling Stones are back at No 1 in the charts with a remastered version of their classic album Exile on Main Street.

It is a fact that they are at No 1, but can the word "classic" – repeated in relation to this album hundreds of times in the past few weeks – ever be more than an opinion? Stephen Daldry, when he ran the Royal Court theatre, put on a series of "classic plays". When he was challenged about how one of them did when it was first produced, he replied: "Oh, it was a flop." He then raised his eyes to the heavens and asked rhetorically: "Well, how do you define a classic?"

The definition across the arts has to be more than endless repetition of the word. Those watching the very diverting new film of the Stones making the album in the South of France in 1971 should listen out for a few words near the end from former Stone Bill Wyman. He says of Exile on Main Street: "I don't think we had hardly any good reviews. They were all saying it was a load of crap."

He does add that many of those critics later ate their words. Nevertheless, people not born in 1972 might be surprised to learn after the hyperbole of the past few weeks that this classic, this masterpiece, did get poor reviews on its release. Not, of course, that bad reviews and initially mixed reaction preclude a work of art from being a classic. If that were the case, we would have to take The Rite of Spring, Carmen and Ravel's Bolero off the list of classics. But I still wonder exactly when and where Exile on Main Street got the classic tag, which will now be attached to it in perpetuity, and whether there is any agreed criterion in any art form for the definition of a classic.

My own theory in the case of Exile on Main Street is that it doesn't half help if there were film cameras present. Had Mick and Keith thought to have a film director around when they were recording "Sympathy for the Devil" and "Street Fighting Man" on the album Beggars Banquet, or "Brown Sugar" and "Wild Horses" on Sticky Fingers, then I suspect we would now be hailing them as classics, watching the grainy movies at Cannes and leaving Exile on Main Street to its cult status.

For generations to come, the definition of a classic will be easier; the internet, blogs and YouTube will have chronicled critical and public reaction to a work every step of the way. But for now, the definition of a classic seems to be: "It is because we say it is." The "we" is usually a coterie of well-placed critics and PRs for a current project relating to the work in question. Repeat the word classic enough times and few will argue.

Some works genuinely achieve classic status, but many more have classic status carefully thrust upon them.

Not all fans will stand for this

The rock band Limp Bizkit have announced that they are postponing their American tour after being booked into too many tiered seating venues. The band's frontman Fred Durst says: "We like to see less seats in front of the stage and more floor filled with fans going bananas."

I think that is, appropriately enough, a bit limp. It's a lot nicer for a band to see the fans going bananas, but the onus is on the band to get them into a bananas-like state; and at indoor venues, as opposed to festivals, this can be achieved with seated fans just as much as with those in the mosh pit. Rock fans come in all ages and, more pertinently, in all sizes. Standing isn't to everyone's taste, particularly smaller fans who get to see very little.

Let those who want to sit do so, Fred. Once you and the band have them going bananas, they will almost certainly leap out of their seats. That sort of genuine, spontaneous bananas state is surely more satisfying for audience and band.

Shakespeare's trove of agony uncles

I was fascinated and a little alarmed to see on a television news item that 6,000 people a year write to "Juliet" in Verona, at the address where Shakespeare's heroine is assumed to have lived. These letters contain various thoughts about love and relationships, and poor dead Juliet is treated as an agony aunt. No fewer than 60 secretaries are employed to respond to the letters.

But why stop at Juliet? If Shakespeare's characters are to be treated as agony aunts and uncles, then I might start writing a few missives myself. "Dear King Lear, daughters can be really troublesome can't they? You should hear my problems."

"Dear Mr Macbeth, I fear that I lack ambition. Can you advise? If you're too busy, could you please pass my letter on to the wife?"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies