University students have been asking parents for money since the Middle Ages, according to historic letters

Requests for money for buying 'parchment, ink, a desk, rent lodgings, and necessaries' have been all-too-common since around 1200 when one student complained of Oxford being 'expensive'

Parents shouldn’t be alarmed if their children do it over the coming academic year, and students have every right to do it because it’s been happening since the Middle Ages: asking parents for money while at university.

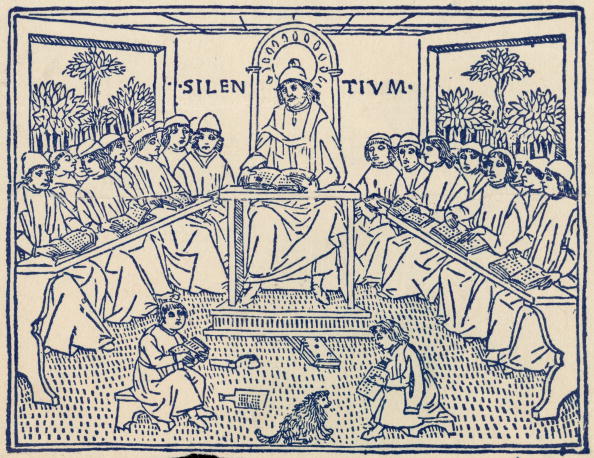

Yes, as hard as it may be to believe, students have been doing it before this generation, and before that one, and before that one too – since around 1220, in fact.

The evidence behind the extraordinary fact has come to light after letters sent by students to their parents resurfaced online, thanks to the Middle Ages blog, Medievalists.net.

First published in Charles H. Haskins’ The Life of Medieval Students as Illustrated by their Letters (1898) – and then discussed further as a recurring theme in Hunt Janin’s The University in Medieval Life, 1179-1499 (2008) – students and parents alike are able to gain an insight into the need for money on campus way back when:

This Oxford scholar wrote home in 1220 to complain how ‘the city is expensive and makes many demands’ – perhaps much like his counterparts today might:

B. to his venerable master A., greeting. This is to inform you that I am studying at Oxford with the greatest diligence, but the matter of money stands greatly in the way of my promotion, as it is now two months since I spent the last of what you sent me. The city is expensive and makes many demands; I have to rent lodgings, buy necessaries, and provide for many other things which I cannot now specify. Wherefore I respectfully beg your paternity that by the promptings of divine pity you may assist me, so that I may be able to complete what I have well begun. For you must know that without Ceres and Bacchus Apollo grows cold.

Unsurprisingly, Ceres was the Greek god of food, Bacchus of wine, and Apollo was known as the god of music. Some things just never change.

Perhaps it was these two brothers in 12th-century France who devised the age-old trick of informing parents of all the great progress being made before making their demands?:

To their very dear and respectable parents M. Matre, knight, and M. his wife, M. and S., their sons, send greetings and filial obedience.

This is to inform you that, by divine mercy, we are living in good health in the City of Orléans, an are devoting ourselves wholly to study, mindful of the words of Cato, ‘To know anything is praiseworthy.’ We occupy a good dwelling, next door but one to the schools and market-place, so that we can go to school every day without wetting our feet. We have also good companions in the house with us, well advanced in their studies and of excellent habit – an advantage which we well appreciate, for as the Psalmist says, ‘With an upright man thou wilt show thyself upright’. Wherefore lest production cease from lack of material, we beg your paternity to send us by the bearer, B., money for buying parchment, ink, a desk, and other things which we need, in sufficient amount that we may suffer no want on your account (God forbid!) but finish our studies and return home with honour. The bearer will also take charge of the shoes and stockings which you have to send us, and any news as well.

Finally, French writer Eustache Descamps (1346-1406) – who went to the University of Orléans – penned this imaginary letter around the year 1400, poking fun at students at the time:

Well beloved father, I have not a penny, nor can I get any save through you, for all things at the University are so dear, nor can I study in my Code or my Digest [these are legal texts], for their leaves [pages] have the falling sickness. Moreover, I owe ten crowns to the provost, and can find no man to lend them to me. I ask of you greetings and money.

The student has need of many things if he will profit here; his father and his kin must supply him freely so that he will not be compelled to pawn his book, but will have ready money in his purse, with gowns and and furs and decent clothing; or he will be damned for a beggar; wherefore, that men may not take me for a beast, I ask of you greetings and money.

Wines are expensive, as are hostels and other good things; I owe in every street, and am hard put to free myself from such snares. Dear father, deign to help me! I fear being excommunicated; already I have been cited, and there is not even a dry bone in my larder. If I cannot find money before this feast of Easter, the church door will be shut in my face; wherefore grant my supplication. I ask of you greetings and money.

Well beloved father, to ease my debts contracted to the tavern, at the baker’s, with the professors and the beadles, and to pay my subscriptions to the laundress and the barber, I ask of you greetings and money.

Overall, parents around the country should take note of one medieval Italian father’s statement to prepare them for academic year 2015/16 – and onwards: “A student’s first song is a demand for money – and there will never be a letter which does not ask for cash.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies