James Lawton: If Tiger is to recover his zip, he should remember how Nicklaus relocated his genius

The fact is Nicklaus also had an early mid-life crisis, and it was one that persuaded himhis winning touch had possibly gone for ever

More and more it is being said that Tiger Woods is lost. It has turned into a clamour. Wherever he turns, there is discouragement.

In Augusta, where he separated himself from the rest of the golfing population as a 21-year-old 14 years ago, he gets some early practice for this week's US Masters and every little breeze riffling the dogwoods carries the news that Phil Mickelson is on fire – and that any number of contenders, even those without a major title between them, fancy their chances.

For the first time in more than a decade, he is not the favourite to win the tournament he has claimed four times and once threatened to own. Some say that the damage left undone by the years of sexual dissipation is being completed by his new, eccentric swing coach Sean Foley.

Where, at 35, does he turn? It is, if he can still think straight, to relatively recent history. It is to Jack Nicklaus.

He goes back to the time when he was a freakishly precocious 10-year-old in Southern California, winning tournaments and stunning TV audiences with his trick shots and, much more relevantly, when Nicklaus, the last man standing between him and golfing immortality, was winning his last major at the age of 46, the second-oldest man in history to perform the feat after Julius Boros, who won the 1968 PGA title.

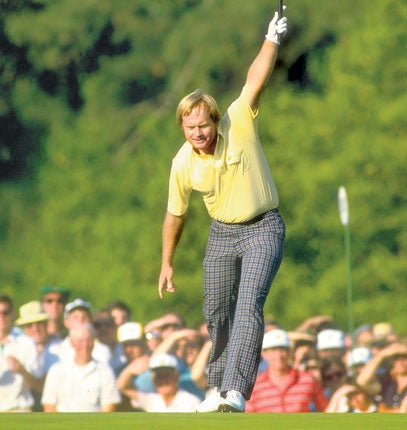

For Woods, this week might just be something more than the 25th anniversary of Nicklaus's extraordinary triumph, when Amen Corner responded thunderously to a late run that carried him beyond such as Tom Kite, Greg Norman, Seve Ballesteros and Nick Price, for his sixth Green Jacket and 18th major title.

It could also provide a vital, inspiring perspective on his unpromising situation.

The fact is that Nicklaus also had an early mid-life crisis, much earlier, and it was one that persuaded him that his winning touch had possibly gone for ever.

He was just 30, five years younger than the Tiger today. He had, like Tiger now, to go back more than two years to his last major win. He was, unlike Woods, overweight and jaded. There was, however, an overriding similarity in his situation. He had lost the man who had driven him to greatness, his father Charlie, who lit braziers on the tees of their frost-bound local course in Ohio and made a driving range of their basement, just as Earl Woods, the old jungle-fighter, made his son his life's work.

In the spring of 1979, as he worked slavishly to build on the recovery that had brought the end of another slump reminiscent of the one he had suffered a decade earlier with a second Open win at St Andrews in 1978, Nicklaus spoke of the impact of the loss of his father, how it had made him reassess his life and his game and what he might do with it.

He was working late into the night on the practice range at the course he built in Ohio. Fireflies performed delicate tracery in the dusk. At one point he chipped deliciously to within an inch of the hole and said, "Goddamit, look at that shot – I can't buy a shot like that in a tournament right now, but I know it's there – you just have to keep working on it.

"I know that now, I know what you have to do but I wasn't so sure back when my dad died." He had managed just four top-four finishes in 14 tournaments, but then yes, he would retrace the origins of his greatness. The following year he won the US Open and the PGA, his 16th and 17th majors.

Darkness had fallen over the course when he walked away that night in Ohio.

"I had tears in my eyes at St Andrews when I won in 1970 because of different emotions but the main one was that my father had died when he must have doubted whether I would continue to be a dominant player.

"I was playing good enough golf but it really wasn't that big a deal to me one way or the other. And then my father passed away and I sort of realised that he had certainly lived his life through my golf game. I really hadn't given him the best of that and so 1970 was an emotional year for me from that standpoint.

"I had to change myself. My weight had gone over 200 pounds. I wasn't fit. I got tired towards the end of a round. There was a simple question I had to ask myself: how much do I want this now, how hard am I prepared to work?"

His answer was, of course, relentless: 11 more majors, the last one coming at a time when his young rivals liked to assume that he had become more of an adornment than a threat. By this calculation, the Tiger has 11 more years to win the five majors that would carry him to a unique place in golf.

Can he find the old nerve – and motivation? Nicklaus discovered it again when he revisited the passion of his youth and the extent of his father's support. The complications of the Tiger's life, a growing sense of alienation from the sources of his brilliance, may not permit such a smooth adoption of a single strength.

But if a sense of betrayal of the best values he had been given was such a mighty spur for Jack Nicklaus, who knows, it might sooner or later work for the one player who threatens his legacy. He certainly has plenty of time, starting this Thursday. Eleven years, after all, should be long enough to solve a case of misplaced genius.

It would be shameful of United to contest Rooney punishment

No doubt there is rage at Old Trafford this morning that Wayne Rooney is to be charged by the Football Association for the obscenity he mouthed in his moment of triumph at West Ham United.

An old persecution complex will be running high and no doubt augmented by the belief that this is a somewhat arbitrary decision in an age when hate, viciously particular, booms down from the terraces and when you don't need a degree in lip-reading to pick up what the old United star Pat Crerand, in another age, once described as "industrial language".

But United, from Sir Alex Ferguson down, need to put their anger aside, and consider for a moment that they have certain responsibilities as the nation's leading football club. One of them is to have their hugely rewarded staff behave in a passably civilised manner. Rooney's language and behaviour in front of a television camera and microphone fell hopelessly below this reasonable demand.

Rooney is not some angry no-hoper on the bottom rung of a fractured society. He lives in a mansion. He is cosseted and made allowances for at every turn. It is no good United, or Rooney (left), saying that his outburst came at the spur of an emotion-charged moment – or that he had been subjected to sickening abuse from the crowd.

Sickening abuse is unfortunately routine business at a football ground. Nor is this the first time Rooney had behaved with less than basic professionalism. Some might say that he is a convenient victim of a Respect campaign which is currently in tatters but then a start has to be made in the uphill job of reminding professionals that they have certain duties.

Responsibilities are too easily shed in today's football, not least by authorities who refuse to address such points of dissension as on-field cheating and frequently inadequate officiating. But this takes us away from a central issue which has now been addressed.

Rooney's behaviour was both crass and unacceptable. This has been recognised correctly by the Football Association. For Manchester United to do any less would be a shameful failure of conscience.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies