Kevin Garside: In this era of pampered professionals the name Muhammad Ali stands out as a hero who transcended sport

Comment

The route from the hotel to the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville leads you smack, bang into the heart of the darkness that shaped America. A plaque marking the site of a Louisville slave pen – there are a few dotted about the city – pointed to the trading floor of the Arterburn Brothers just off Main Street, which today serves as a car park.

It was a reminder of the atmosphere that clung to America’s south way past the day in 1863 that Abraham Lincoln put emancipation on the statutes, a reminder of the oppression and prejudice that existed in the appalling culture of American apartheid into which one Cassius Marcellus Clay was born.

Even now, almost 50 years after he raised his hand in protest, stood up to the state apparatus, put his career on the line, the remarkable resistance of the boy who became Muhammad Ali takes the breath away. An hour at the Ali Center is all the time you need to smash through the blurred lines of sport and celebrity that cocoon our heroes today.

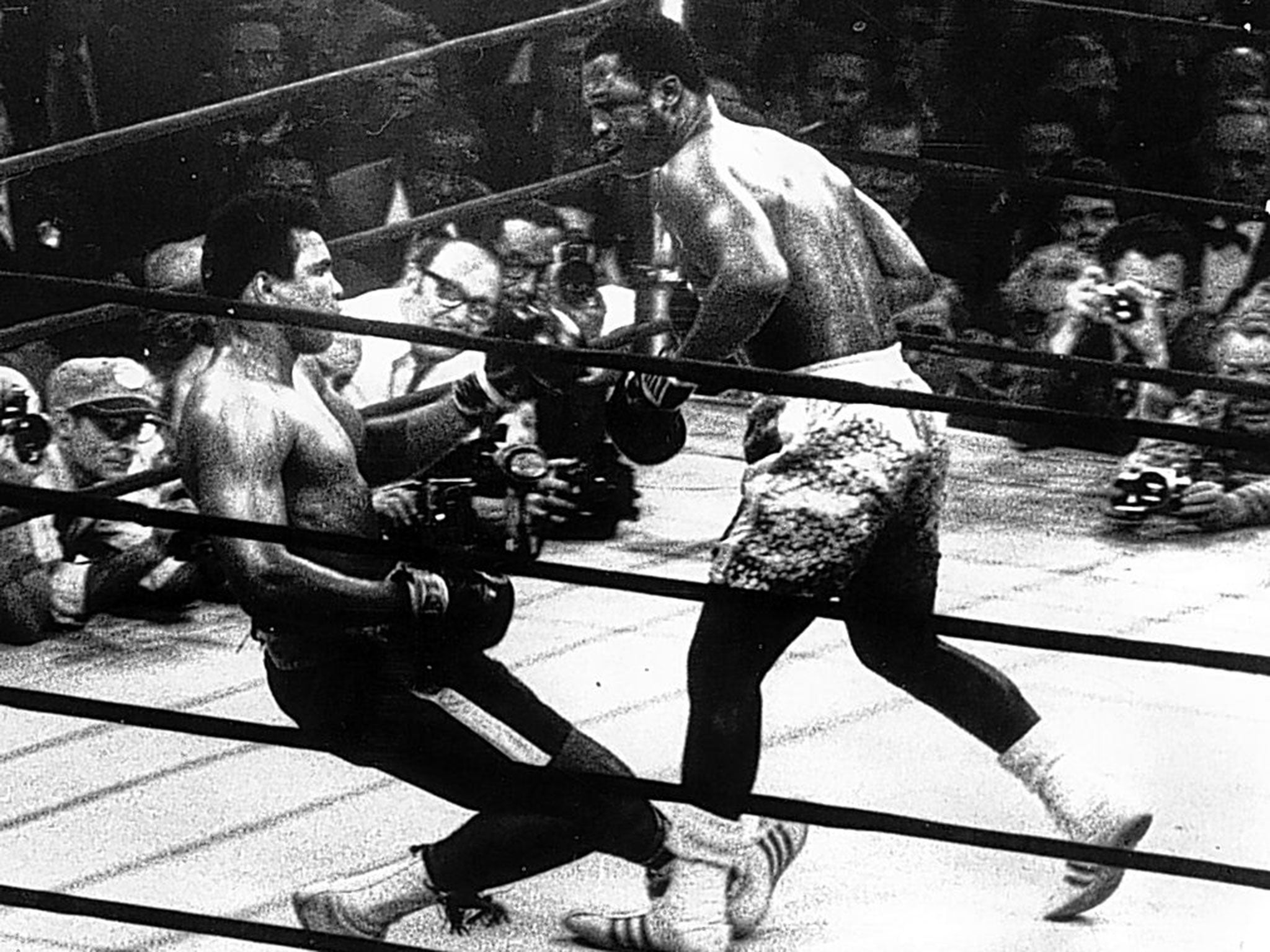

Those epic, era-defining contests with Joe Frazier, George Foreman and Ken Norton were enough to elevate Ali to the highest table of heavyweight boxing, placing him alongside the likes of Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey, Gene Tunney, Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano, and as thrilling as it is to revisit that part of his story, it is not the element of greatest import.

Ali was arguably past his athletic peak when he walked into Madison Square Garden in 1971 to face Frazier for the first time. The brash 22-year-old kid who took down Sonny Liston for the first time seven years earlier really was a beautiful piece of work, as fine a specimen as ever laced a glove. Again his athletic genius was only half the tale. The character of the man would emerge between Liston fights when he shed the Clay persona and its slave associations that tradition handed down, to become the 20th century’s greatest sporting figure.

The short film overlaid with the voice of Maya Angelou at the start of the museum tour lays out the journey from passive disquiet to full-on political engagement, the embrace of Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm X at the heart of the civil rights movement and the moment he presents his chin to the American political class at Houston in 1967, refusing three times to step forward at the call of his name during the draft induction process to the US Army. Oh My God.

The exchange with the outraged white boys who could not comprehend how anyone might refuse to fight for his country has lost none of its power, especially the look on their faces, and his, when he asks them to consider why he should fight for a nation that refuses to come to his defence when his civil rights are under attack from his own political masters.

This was a time when African Americans in Louisville and elsewhere across the southern states faced segregation in every aspect of their lives, a time when he was not free to engage in even the simplest of things in a public place, like eating a burger in the company of white men, for example.

The lithe warrior who danced to Olympic gold in Rome in 1960, who broke the mould with the double dispatch of Liston in arresting displays that were both brutal and balletic, was denied us in his physical prime. He was absent from a professional ring for nearly four years from 1967 until his appeal against suspension was upheld.

The museum wasn’t busy. It was the last hour of trading on a quiet Wednesday afternoon. A French family were among the few stragglers seeing out the day by the Ohio River. Dad probably dragged them in. While he combed the corridors taking everything in, his two teenage daughters sat transfixed before a film of the second Norton fight.

Ali held the centre of the ring, adopting that beautifully balanced, classically wide stance of his and firing the rapier jabs from which all else flowed. Ali lost their first bout in 1973 after sustaining a broken jaw early in the bout, which infused the rematch with a heightened sense of importance capable of absorbing a young, French audience two generations on.

Ali edged their second fight. Norton went on to face Foreman and was blitzed inside two rounds. From there all roads led to Zaire in 1974, when Ali defied time and the beast in Foreman to deliver a result that defied convention. He wasn’t supposed to win, he couldn’t win, but win he did.

Though little is seen of Ali these days, his devotees in the centre claim he is in good shape. Let us hope he sees out his battle with Parkinson’s with all the comfort he can muster and remember him as the towering champion he was, in and out of the boxing ring.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies