Flora Illustrata is much more than a straight history of flower painting

The history of how the herbal, or plant encyclopaedia, came into being is a surprisingly rich one, says Anna Pavord

Bombarded with images of plants, as we are now, it is difficult to imagine a time when there weren't any. It seems odd that it took so long for a picture to be attached to a description of a plant, and so join one way of absorbing information with another. From early times, plants had been used in decorative schemes: myrtle and roses on the walls of villas at Pompeii and Herculaneum, saffron crocus, iris, Madonna lilies on frescoes at Knossos.

But then someone, somewhere, had the idea of using illustrations alongside text, so that plants could be more easily identified.

The Roman author, Pliny, made the earliest reference to illustrations around 77AD, but recognised the difficulties: plants had many colours, the painters in the early days had few. The palette was limited to one kind of green, a blue, a coffee-coloured brown for the roots, and various ochre-based yellows and oranges for the flowers. He made another important point. "It is not enough," he wrote, "for each plant to be painted at one period only of its life, since it alters its appearance with the fourfold changes of the year." It took a long while before artists realised that that problem could quite easily be solved.

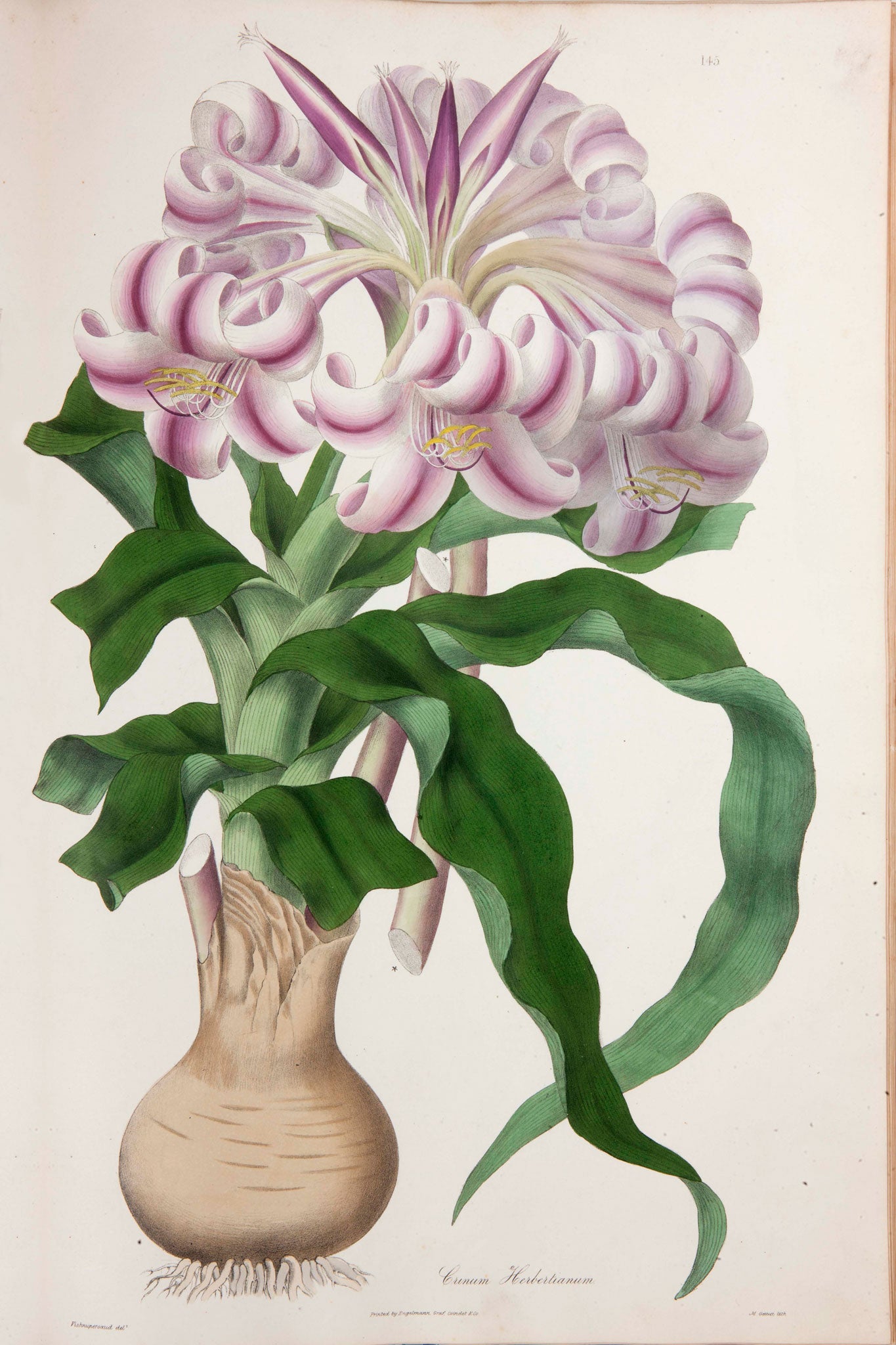

The earliest pictures are single snapshots, the plant in its prime with roots, stem, leaves and flower all present. Early illustrators were particularly keen on showing roots. At a time when plants provided most of the available medicines, roots were regarded as the most essential, and therefore, the part of the plant most likely to do you good.

For us in the West, the change began at the end of the 13th century when, for the first time, an unknown artist decorated the pages of a herbal made probably in Salerno between 1280-1300 (it's now in the British Library), with portraits of plants that danced and sang and knew their names. Summer jasmine, a Madonna lily, its boat-shaped, pollen-loaded anthers perfectly captured, vines, a pine tree... the plant portrait had arrived. Pictures had overtaken words as a way of describing plants accurately. Those who wrote about plants were still churning out bad translations of the ancient texts. Artists were looking nature straight in the face and showing plants exactly as they appeared before their own eyes.

But why was it that artists could see those blooms, describe them on paper, while the writers remained dumb? It was almost as if artists such as Dürer (who painted the famous piece of turf) was living in a different world to those who used words rather than paints for their pictures. Artists had been able to forge a new language of painting. Writers were slower to create the new vocabulary they needed to describe things. Even the simple word 'petal' didn't come into the language until 1592, suggested by an Italian scholar, Fabio Colonna.

Plants had originally been painted because they were useful. But gradually, artists began to paint plants because they were intriguing and beautiful, not just because some doctor or apothecary needed to be able to identify it And with the invention of printing, a new age arrived: fabulous plant books with hand-coloured illustrations, that now command equally fabulous prices. Five million dollars was paid for a copy of Les Liliacees (1802) illustrated by the famous Pierre-Joseph Redouté; four and a half million dollars was the price of a Treatise on the Fruit Trees (1768) with hand-coloured engravings by Pierre Antoine Poiteau and Pierre Jean François Turpin.

Only 125 copies were ever published of the spectacular Orchidaceae of Mexico and Guatemala put together in the middle of the 19th century by James Bateman. Only 25 sets are known to exist of the equally fabulous Flora Graeca, published in 10 volumes between 1806-1840. But in the New York Botanic Garden's extraordinary library, you'll find both these books, among about a million others.

This world-class collection is celebrated in Flora Illustrata (Yale, £35), a gorgeously designed and illustrated book that is much more than a straight history of flower painting. The first part tells how the library was first set up, with books donated by eminent American botanists such as John Torrey and the Lyceum of Natural History in New York. Then comes a mouth-watering selection of the great European herbals and flower books that, once printing had been invented, were produced in a dazzling number of editions.

The first bestseller, the first printed plant book to be read throughout Europe, was produced in 1530. The key to the book's success was not the words, still mostly cobbled together from Classical texts, but the woodcuts contributed by Hans Weiditz, draughtsman, engraver and pupil of the great Albrecht Dürer, who like his master, drew direct from life. He created the first printed images of plants – Pasque flowers, violets, waterlilies – that could be recognised in any country in Europe.

The second half of Flora Illustrata deals with less familiar territory and tells of the long and difficult process of producing a truly American flora. Books about plants of the New World began appearing in Europe early in the 17th century, but another 200 years passed before the American John Torrey could draw together enough of the information scattered in various herbariums and private collections to publish in the US his Flora of North America.

It is an extraordinary story and not one I understood before it was all explained in Flora Illustrata. The New York Botanic Garden Library has all Torrey's papers, as well as the beautiful black-and-gold tin flask (vasculum) he used to preserve plants when he was out on collecting trips. They also have a vast collection of American nurserymen's catalogues, tracking exactly who was selling what and to whom, and extravagantly illustrated with pictures, from The Best Lettuce in the World, to the perfect layout for a Family Fruit Garden. This is the most beautifully produced book I have seen for years: thick paper, wide margins, elegant typography, perfect reproduction of colour. Kindles, creep now into a dark corner and weep.

WEEKEND WORK

WHAT TO DO

* I have three pots of cymbidiums, all rather big. All get exactly the same treatment yet one is plastered with spikes of bloom, one is just earning its keep, while the third has no flowers at all. Why?

* If a cymbidium is producing sheaves of healthy leaves, but no flowers, the general view is that it's getting fed too much. Then you're supposed to keep it watered, but avoid feeding for three or four months. So I'll try that and see what happens. I'm also going to start noting how many flower spikes each plant has each year. It may be, with plants as with people, that some are more inherently generous than others.

WHAT TO SEE

* The winter lecture series organised by the Oxford Botanic Garden starts on 29 January with a talk by landscape architect Kim Wilkie. John Grimshaw, the charismatic director of the Yorkshire Arboretum, stresses the importance of diversity in tree planting in his talk on 12 February. Tickets are £12 or £54 for the series of five lectures. Lectures take place at the Said Business School, Kennington Rd, Oxford OX1 5NY. For tickets call 01865 286690 or visit botanic-garden.ox.ac.uk

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies