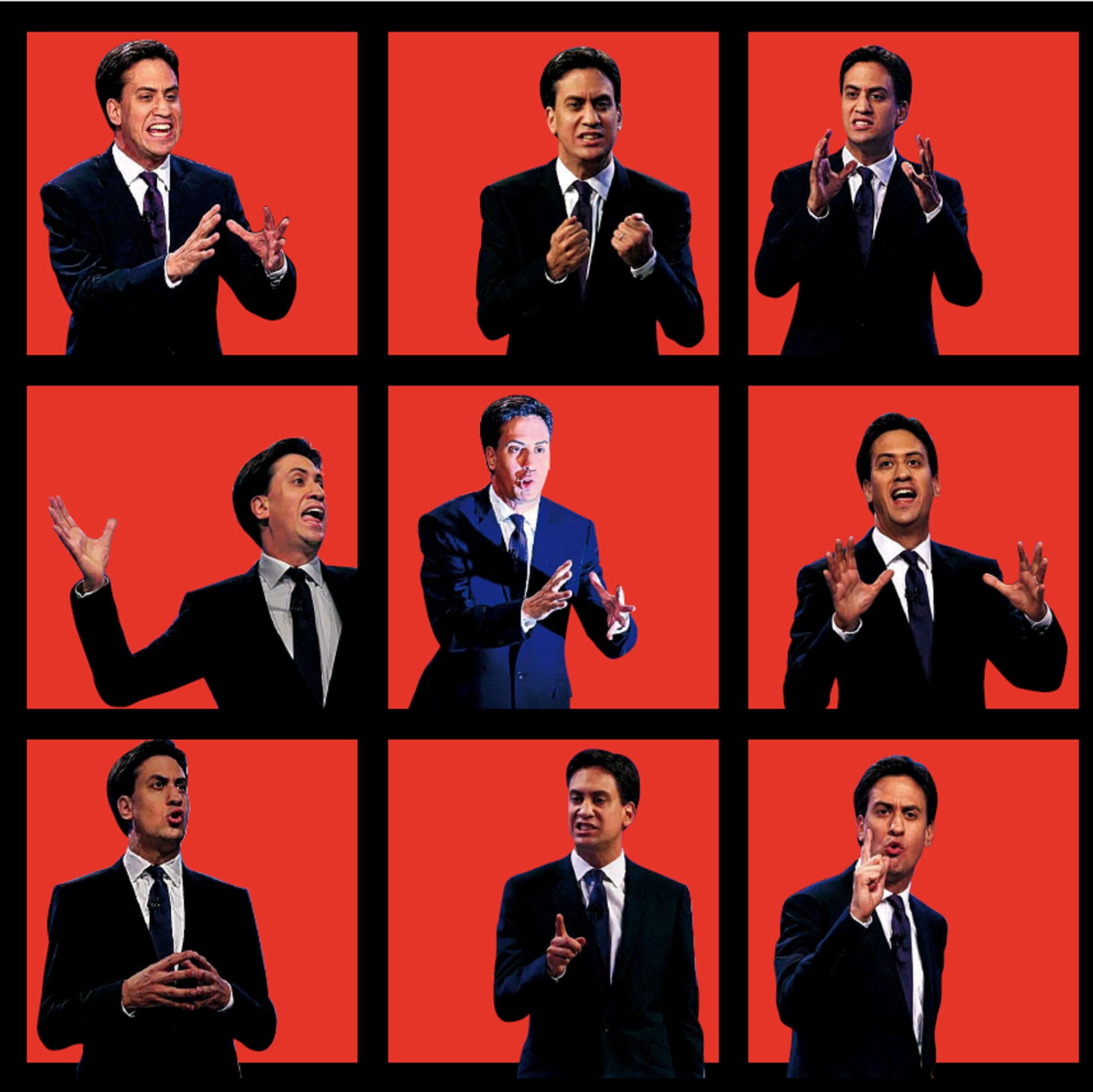

An in depth look at Labour conference week: Ed Miliband's speech - did you hear what I heard?

Commentators' determination to link the Labour leader to a decade they revile, the Seventies, reveals more about them and little about what matters to many of us

Ed Miliband's speech to the Labour Party conference was given in Brighton last Tuesday but, to read many of the newspapers the next day, you could have been forgiven for thinking it had been delivered outside a colliery in about 1977. Despite the trappings of modernity – the dropped consonants, the self-deprecating humour, the roaming, noteless delivery that is these days de rigueur – the general view of the speech was as a throwback to the Seventies. "Red Ed", as he has witlessly been called again in an image that harks back even further, was firmly saddled with the baggage of the past. A leader for the 21st century? Ha! As far as most of the commentariat is concerned, Miliband might as well have bounced into the venue on a space hopper.

With the possible exception of glam-rock enthusiasts, there are very few people who would consider that set of associations to be a positive one. And the right-wing press, it is safe to say, is not yearning for a reprise of T Rex's greatest hits. Some paid grudging respect to the speech as a tactical move, but very few were happy about it. "On this evidence," Dominic Sandbrook wrote in the Daily Mail, "Ed Miliband's ideal society looks worryingly like the seedy, shabby, downbeat world of Britain in the mid-1970s." In The Daily Telegraph, Jeremy Warner gloomily concluded that, "Red Ed is, I fear, just reverting to type". His headline summary of the Labour leader's message? "Get out the flares."

Among newspaper editors and commentators, this interpretation apparently resonated. Whether it will be quite so compelling to the general public is another matter. Personally, I found it all a little baffling. I had sat through the whole speech and found it, well, roughly the same as most political speeches: a surprisingly plausible simulation of the kinds of things that an actual human being might say, if you made generous allowances for the jokes and catchphrases and mannerisms – a bit like Bruce Forsyth giving a eulogy. At no point, even as Miliband told us about his headline-grabbing plan to freeze gas and electricity prices, did I find myself thinking of Jim Callaghan and Harold Wilson. And that's probably because I don't remember them.

As a twentysomething, a line I intend to repeat as often as possible for the week it remains available to me, my sense of the Seventies is not formed by direct exposure. Instead, it's a hazy montage of children's animated series produced at a shockingly low frame rate in washed-out colours, perhaps narrated by Noddy Holder. BBC3 clip shows have inculcated a vague sense that white dog poo might have been a feature. I think of hardnut footballers in tiny shorts. Economic deprivation, the visit of the IMF, and a properly Marxist wing to the Labour Party are all in the mix somewhere, too. But it is a self-centred fact of life that such serious matters do not carry much cultural weight, do not tend to outlast their time in popular memory.

This is not a question of policy. I don't really know enough to give an original view on the wisdom or otherwise of Miliband's plans for the energy market. But there's another important discussion to be had about the way we frame the argument. We tend to make a lot of our political points by analogy, and so the choice of comparison is not only important for its accuracy but for what it conveys to the audience. If you think we need to talk more about politics as a whole country, and less as a series of discrete voter blocs, this matters. So what does this bell-bottomed historical perspective convey? Who is applying it, and why? And what sort of effect will it have on the debate?

One way to begin to answer those questions is to do a bit of basic maths. The sludge-tinted nostalgia to be found in Wednesday's press (and just as prevalently in the broadcast punditry which had preceded it) is presumably predicated on the idea that such associations will be widely evocative. But suppose you say that, to have a meaningful first-hand understanding of what the currents of the Seventies felt like, you have to have been politically conscious by late 1978, for the beginning of the Winter of Discontent, and suppose that you set the benchmark age at which one gains that sort of awareness at 10 years old. This is an extremely optimistic assessment; show me a 10-year-old who is interested in politics and I will show you someone who will go on to attend party conferences, which is to say, someone who is not normal.

Still, for the sake of argument, agree that anyone born in 1968 or before is keenly aware of the days of Callaghan and co. Those people are at least 45 now; anyone younger came of age in the era of Margaret Thatcher or even later. Ed Miliband himself, 43, talked in his speech about what it was like growing up in the Eighties. When even a party leader is too young to remember the political era you're talking about, you might start to think it's a little dated.

I suppose I could be accused of biastowards the interests of this younger cohort. But, God knows, there are more than enough columnists erring in the opposite direction. And while the voting population skews older, it doesn't skew much older. The median voting age in 2010 was 49. Besides, even among that contingent, Labour loyalists are unlikely to be put off by memories of the three-day week; the corresponding Conservatives have likewise already made their minds up. The relevant audience is therefore limited to a rump of older swing voters. And some of them will remember things differently anyhow. Some of them, too, may think more readily of Tony Benn – the animated one – than Denis Healey. Some of them – and this will seem shocking to those who live and breathe politics – might just not remember it all that well, full stop.

It's not that the punditocracy should deliberately shape its views to appeal to the broadest segment of society; nor that an analogy is necessarily inaccurate simply because most people are ignorant of it. But it does remind us of how easily the impression of consensus can be given when no such consensus exists. The term "socialist" has repeatedly been attached to Miliband, not least by himself, and its easy coexistence with the "Red Ed" epithet suggests that his many critics deem this a slightly retro thing to be. Miliband, we are told, has used his time machine to vacate the "centre ground". And yet, as some left-wing commentators seeking to puncture the prevailing theme have pointed out, Miliband is to the right of public opinion on a number of issues on which he is caricatured as an extreme left-winger, from the renationalisation of public utilities to the level of the minimum wage. As the New Statesman's George Eaton put it: "If Miliband is a socialist, then so are most of the electorate."

Since public opinion would also like to pay no taxes and have brilliant public services, it would be a mistake to rely on it as a guide to economic policy. But it would be equally asinine for a left-leaning politician to ignore it. Miliband is placing what seems to me like an astute bet: voters are so used to the language of managerialism which permeates today's politics, so far removed from the Seventies radicalism which looms so large in the collective memory of the commentariat, that any political move which seems to be born of idealism will seem refreshing.

Meanwhile, although he has identified himself as a socialist – and, really, in a party expressly committed to the ideals of democratic socialism, it would be a little peculiar not to – he will not repeat the term too often, just in case the loony-leftie characterisation sticks. (By "sticks" I don't mean with his critics in the press, but with the wider public.) Some have noted similarities to Tony Blair's 1997 windfall tax on utility companies, a move that created a £5bn fund to help get the unemployed back into work but escaped the Marxist shtick. On Twitter, Alastair Campbell has defined this energy plan in similar terms, as a move towards "putting the consumer first" – "more New Deal than Old Labour". The word "consumer", so symbolic of post-ideological modernity, is both ugly and telling. Whatever the truth about the precise location of the policy's origins, if people agree with the venerable spin doctor, Ed Miliband might start to feel quietly confident about his future in Downing Street.

Peter Mandelson, for his part, disagrees. He saw the speech as a step "backwards" – that is, back towards the decade that haunted Labour for so long. To say so was a striking piece of indiscipline for such an inveterate political operative, but as a member of the Young Communist League in the early Seventies, it is perhaps understandable that the vulpine peer now looks back on that era with a shudder.

Of course, Mandelson's perspective is flawed, as everybody's is, by his inescapable allegiance to his own life story as the whole history of the world. Probably because it makes us feel old and mortal to do so, we too often forget how very ancient the past seems if you did not live through it, all of time compressed into one long instant just before your own birth. For a little while, I've marvelled that a child born today will see 9/11, a luridly formative event for me, as being as impossibly distant as I find the decimalisation of British currency. Everyone will have a corresponding index of their own insignificance.

To see this is, perhaps, to become more sceptical about the value of analogies as argumentative tools – to hope, instead, that we might talk about why ideas are sensible or not on their own terms, today. The truth is that the era that worries Mandelson and so many of his contemporaries so much is receding into being a generational psychodrama, rather than a national one. For better or worse, this is now a debate about the country's future. It would be more productive for everyone if we could start by acknowledging it as such. Dog poo, after all, has not been white for an awfully long time.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies