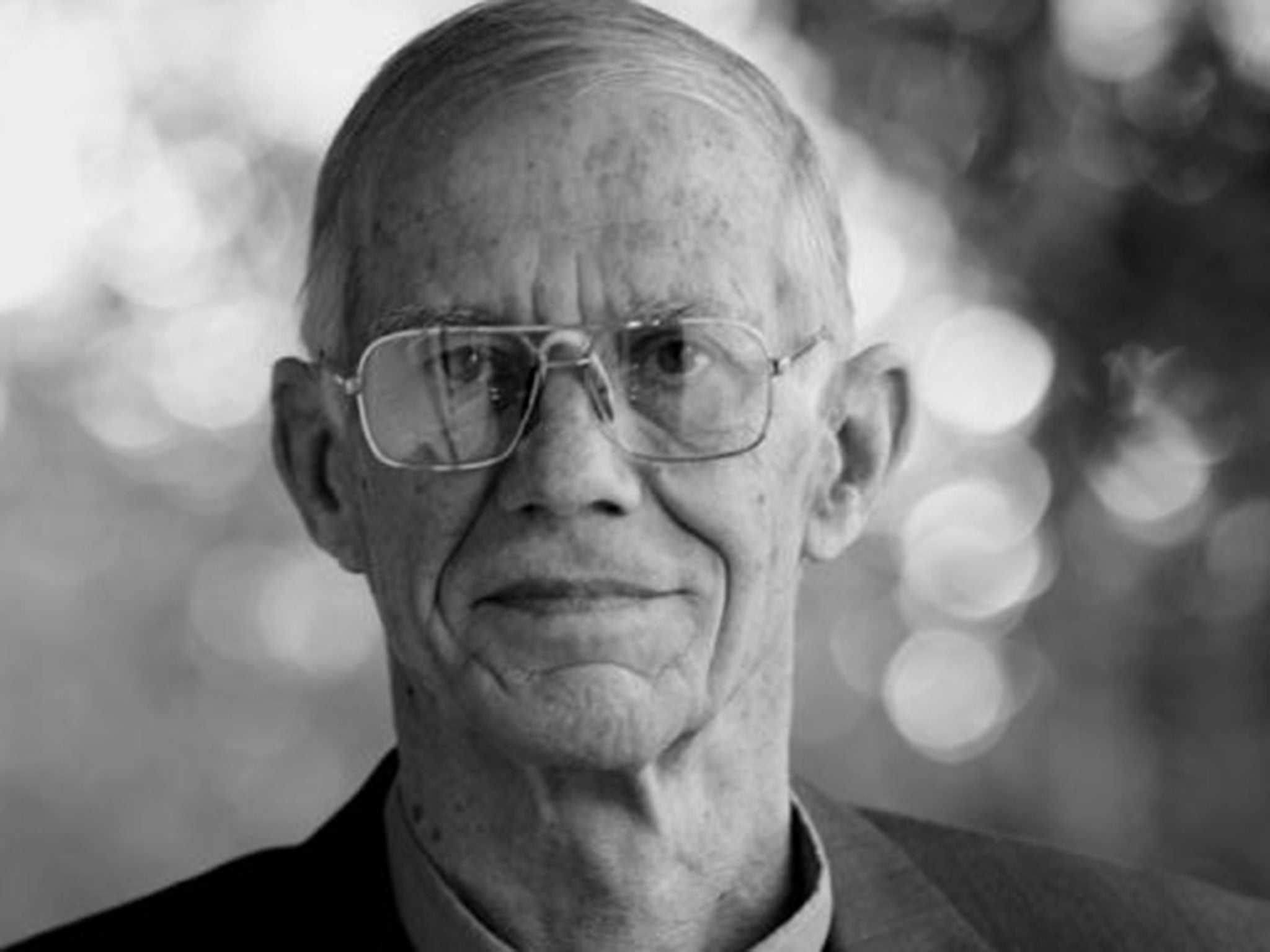

David Russell, Anglican priest: Activist who led movements within and outside the church to help bring an end to apartheid

Russell was ordained as an Anglican priest at the age of 27 and began his ministry in the rural Eastern Cape town of Keiskammahoek, working mainly with poor black parishioners

The final demise of apartheid came from a million pinpricks, and a fair number of these were delivered by people who identified themselves as Christians.

They came in different guises – Catholic liberation theology activists, Protestant anti-war protestors and outspoken Anglican clergy. It could be said that David Russell combined all of these roles over the last two decades of white rule – the most troublesome of all the country’s “political priests”.

He grew up with his twin sister Diana and three other siblings in a well-to-do, intellectually inclined family. Their father, Hamilton Russell, was an MP from Jan Smuts’s United Party who crossed the floor to join the Progressive Party in 1959, while their mother, Molly, was a devoted liberal – so they were raised to question authority.

He was schooled at the elite Diocesan College (“Bishops”), and after graduating from the University of Cape Town completed an MA at Oxford. By then he had a firm sense of vocation – as a socially active Anglo-Catholic – and received his theological tuition through the Community of the Resurrection in Mirfield, Yorkshire. He later completed a PhD in Christian ethics.

Russell was ordained as an Anglican priest at the age of 27 and began his ministry in the rural Eastern Cape town of Keiskammahoek, working mainly with poor black parishioners. He set about learning their language, isiXhosa, and within a few years had reached a level of fluency that amazed native speakers. He later taught isiXhosa to students, partly because he felt that white opponents of apartheid should identify with the experience of the majority.

Russell’s next appointment was as parish priest in King William’s Town, and it was there that he first met Steve Biko. They became close friends and allies, Russell adopting Biko’s black consciousness stance and taking a more directly confrontational stand against apartheid.

He shocked many in the church by fasting on the steps of Grahamstown Cathedral and later moved to the black “location” of Dimbaza, where he lived off the rations the government allocated to people who had been forcibly removed from white areas, drawing attention to their plight with reports from the frontline.

The church appointed Russell as its chaplain to migrant workers, and he used this perch to campaign against forced removals of black people from white “group areas”. When the state demolished people’s homes in Modderdam in 1977 he led a group who lay down in front of the bulldozers. He also worked closely with the squatters from the Crossroads settlement outside Cape Town, helping to set up a clinic.

His form of non-violent direct action had a number of spin-offs, including helping to inspire conscientious objectors who refused to do their military service – a stand that Russell strongly backed at a time when it was illegal.

Until then, the state had tended to treat white clergy with caution, but Russell was considered too much of a danger, and later in 1977 they issued him with his first five-year banning order (a form of house arrest), which he constantly defied. In 1980 he was sentenced to three and-a half years in prison (with two and a half suspended) for breaking his banning order, and spent a short time in Pollsmoor Prison.

He remained under banning orders until 1986, but this seemed to have little effect on his willingness to confront the state; he continued to write, campaign, and attend meetings with conscientious objectors and others while insisting that a priest’s role did not include joining political organisations (which meant he avoided identifying with ANC-aligned groups).

This might have helped him in his campaigns within the Anglican church, where colleagues described him as a crafty strategist who knew how to engage with power structures. For example, he worked behind the scenes to successfully oppose the presence of uniformed Anglican chaplains in the army, and also helped secure controversial church resolutions in the early 1980s declaring apartheid a heresy, supporting conscientious objectors and opposing the role being played by the military.

Sid Luckett, a former Anglican minister and anti-apartheid activist, said his friend led a disciplined and well-organised life, which helped him when he was under heavy surveillance. “I remember vividly our weekly meetings in a back room of his mother’s house, where there were no telephones to be tapped. Every meeting started with a prayer, followed by him pulling out an agenda neatly written on a small piece of paper from his shirt pocket. And we would go through this agenda item by item.”

Luckett says that they sometimes disagreed on theology and politics, but shared the liberation theology view that the church should demonstrate “a preferential option for the poor”.

“David was probably the bravest and most consistent of all the clergy I knew in this commitment – one of the most courageous and principled people I ever met,” he said.

In 1986, soon after Russell’s friend Desmond Tutu became Archbishop of Cape Town, he was appointed Suffragan bishop in the Diocese of St John’s, and a year later Bishop of Grahamstown, a position he held for 17 years. He was diagnosed last year with bone marrow cancer.

David Patrick Hamilton Russell, priest and activist: born Cape Town 6 November 1938; married Dorothea Russell (two children); died Cape Town 17 August 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies