A single question now dominates the economic debate: when should the Bank of England raise interest rates? The arguments in favour of raising interest rates now (or at least soon) can be broken down into three broad categories: normal, slack and risk.

First, let’s deal with “normal”, which is easily the least compelling of the trinity. Some claim that because the economy is now growing at a normal pace again – an annual rate of about 3 per cent – it must be time for monetary policy to return to a “normal” setting. There is no case for emergency rates of 0.5 per cent, goes the argument, when the economy is no longer in an emergency.

But this line of reasoning ignores what a catastrophic blow the global financial crisis was to the economy and living standards. The level of GDP has now, just about, returned to its pre-crisis peak. But this means that, over the past six years, the economy has not grown. At the same time the population has carried on increasing. Output per head of population is still more than 5 per cent below where it was in 2008. Real average earnings are some 8 per cent lower than their level before the financial crisis. This is an odd definition of “normal”. A prolonged period of strong growth is precisely what the British economy needs to recover some of those acres of lost ground. Is this really the time for policymakers to seek to slow things down through tighter money?

Then there are the “slack” arguments in favour of rate rises. Some say there is no spare capacity in the economy and so rock-bottom rates are about to unleash a damaging inflationary spiral. This is strange because consumer price inflation, at 1.5 per cent, is now well below the Bank’s 2 per cent target and there is no sign in the official figures of any pressure on prices from nominal pay increases. The Monetary Policy Committee doesn’t take the view that there is no spare capacity in the economy, but some members think the slack is being rapidly used up. Their argument is that inflation might be low now, but it could pick up rapidly if tightening is left too late.

The trouble is that no one actually knows how much slack there is in the economy. This isn’t something than can be directly measured like unemployment or wages. It can only be guessed at with the help of surveys, theory and anecdote.

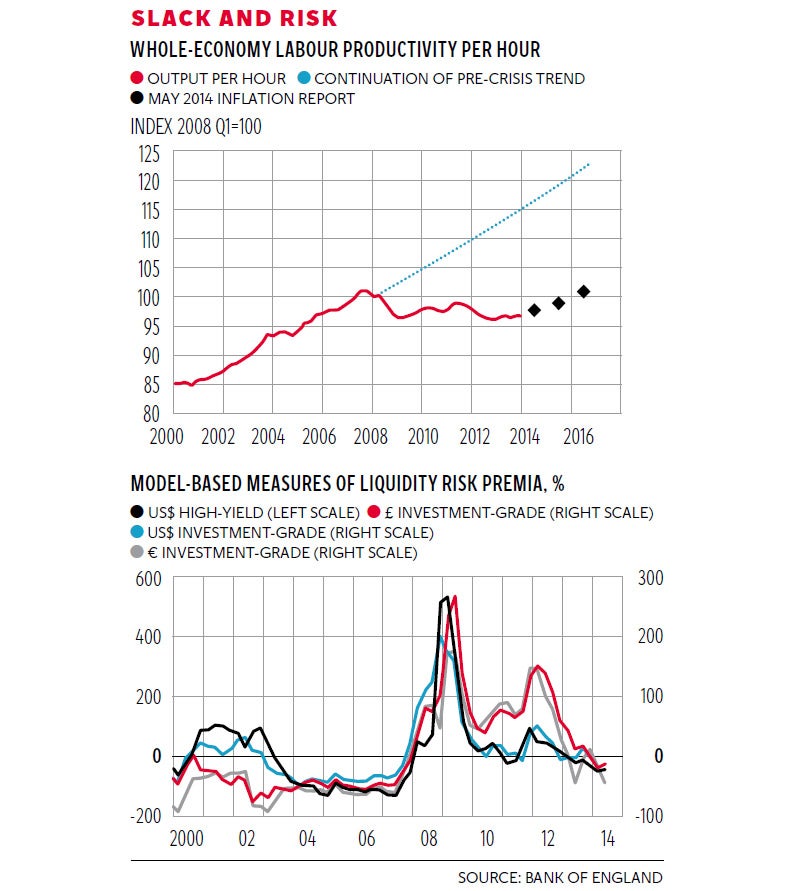

There are many ways of making the case that there remains a considerable degree of slack in the economy, but the simplest and, to me, most compelling is to consider productivity growth in the economy before the financial crisis. Productivity growth was running at around 2.5 per cent per year in the decades before 2008. But following the financial crisis output per hour has flat-lined, as the first chart shows. Why would that have happened? There certainly was some froth from the financial sector in the years before the crash and some structural changes in the economy (in particular dwindling oil output) have dragged it down since.

It is also feasible that there has been some misallocation of resources due to the impaired banking sector. But it stretches belief to imagine that all of that pre-crisis trend potential productivity growth has been lost forever and will not be recouped now that demand is back. Incidentally, the diamonds in the first chart show this is the Bank of England’s baseline view. Productivity does start rising, but it does not head up to the previous trend line. The Bank’s baseline is thus inherently pessimistic on productivity and slack.

Finally, there are the “risk” arguments. The Bank’s latest Financial Stability Report points out that liquidity premiums on corporate bonds and other assets have been pushed down to potentially dangerously low levels as investors “search for yield” in a global low interest-rate environment (see second chart). One common argument is that central banks should tighten monetary policy in order to encourage markets to price assets more sensibly.

But this gets things the wrong way around. The answer to a perceived mispricing of risk by markets is to take regulatory action to ensure the financial system is capable of absorbing a sharp correction without going into meltdown. This means central banks requiring systemically important financial institutions to hold bigger capital buffers. Otherwise policymakers will be calibrating rates in order to guide the behaviour of financial markets, rather than serving the broad needs of the real economy.

Some members of the MPC have suggested it would be better to start raising rates early and gradually, so as to avoid the need to hike them significantly, in a rush, later on, something that would prove much more economically harmful. But one could point to a different risk calculus. Policymakers have experience over the decades of successfully applying the brakes to overheating economies. But the agonies of Japan show that it is much more difficult for authorities to reflate an economy again if policy is tightened prematurely.

The international context is also relevant. The value of sterling, weighted by our trade, has already risen by about 12 per cent over the past year. That is unhelpful for the economy’s rebalancing towards manufacturing and exports. Early rate rises would push the pound higher – especially while the eurozone, Japan and the US are still some distance from tightening.

There remains a great deal of inescapable uncertainty over the UK economy and, thus, the Bank’s appropriate monetary policy stance. But the most serious risk still seems to lie in moving too soon rather than too late.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies