The Big Question: What is short selling, and is it a practice that should be stamped out?

Why are we asking this now?

It has emerged that Morgan Stanley, one of two huge investment banks that has been helping HBOS to raise £4bn from shareholders, was at the same time selling the company's shares short – betting that the Halifax Bank of Scotland group would fall in value. Morgan Stanley has not broken the law, or breached any City rules, but its dealings have certainly raised eyebrows. And this is the latest in a series of controversies in recent months relating to short selling.

What is short selling?

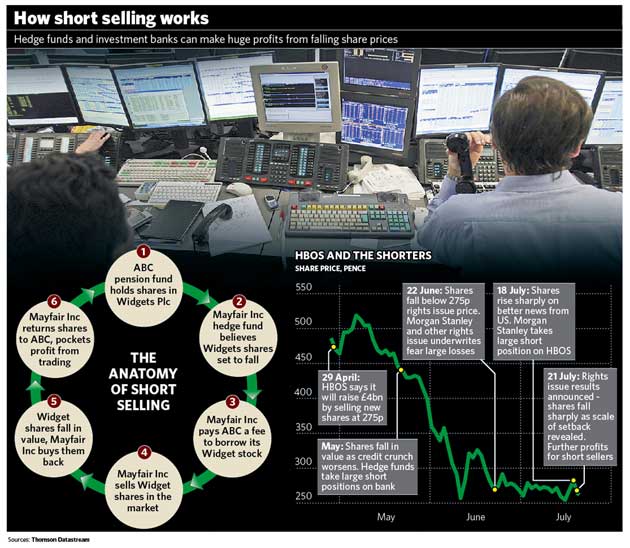

It is a way of profiting from a fall in a company's share price. Most stock market investors buy shares in the hope and expectation that their value will increase – "going long" in the jargon of the City – but it is also possible to make money when the opposite happens. Shorting means selling a share that you don't own in order to buy it back once it has fallen in price, netting a profit in the process.

How can you sell something you don't own?

In a conventional short sale, the investor – usually a hedge fund or large investment bank – takes the view that shares in a particular company are set for a fall. The investor then borrows the shares from someone who does own them – most often a large pension fund or insurance company – and sells them in the market. Once the shares have fallen in value, the investor buys them back at the lower price and returns them to the lender.

If all goes according to plan, the investor is paying less to buy back the shares than it received for selling them. There are some costs involved, notably that the lender charges a fee for loaning out its shares, but in an ideal world the shorter still makes a tidy profit.

There's a variation on this theme, known as "naked short selling" – a form of shorting where the investor doesn't even bother to borrow the shares it is betting against. This is possible because share deals are often not settled immediately. The seller promises to deliver the stock after a short delay – say three days. If a short seller buys the stock back before it has to make good on the original delivery, no shares need actually change hands.

So what's all the controversy?

The biggest concern is that short selling has often been associated with market abuse. The clearest victim of such abuse was HBOS itself, earlier this year. Over the course of just an hour one day in March, its shares plunged when rumours swept the stock market that the bank had financial problems similar to those that caused the collapse of Northern Rock. The rumours were totally false and the share price recovered later in the day, but not before investors with short positions in HBOS shares had made a handsome gain. City regulators are still trying to discover who started the malicious gossip about HBOS, but there is widespread suspicion that the rumours were planted by a hedge fund keen to make a fast buck. Such behaviour is illegal, but also very difficult to investigate.

What about Morgan Stanley?

The ethics of Morgan Stanley's shorting of HBOS is much less clear-cut. The investment bank knew that if HBOS's fund-raising was not a success, it would be held to a promise to buy the bank's shares at a higher price than their prevailing market value, booking a nasty loss. Selling the shares short was one way of making some of these losses back.

Morgan Stanley argues that its shorting of HBOS was sensible risk management, conducted by a separate department to the part of the bank handling the fund-raising. But HBOS must wonder why a bank to which it is paying considerable sums for work on its fund-raising has been simultaneously making money from a fall in its value. It's also clear that by Friday, when Morgan Stanley began shorting HBOS shares in a major way, it knew that the fund-raising was going to be a serious flop.

Any other problems with this practice?

Critics also have little time for pension funds and insurance companies that facilitate the process by lending out their shares. These large investors buy shares on behalf of their clients – you and me – and presumably hope they will rise in value. So it seems bizarre that they're prepared to lend stock to people who want to make money from falling share prices.

The pension funds' argument is that they buy shares with a long-term view. The sort of short-term ups and downs caused by short sellers does not affect this, and besides, they say, they make money for clients from stock lending. Still, in the worst cases, short selling can totally destabilise a company, damaging its prospects for years to come.

What sort of money is involved?

The hedge funds and investment banks that dabble in short selling do so with astronomical amounts of money. Analysis conducted by The Independent shows that hedge funds have made more than £1bn betting on a fall in HBOS's share price in the past two and a half months. One single hedge fund is thought to have made £1bn betting on the collapse of Northern Rock last year.

Remember that stock-market investment is a zero-sum game. For every pound of profit made by a short seller, there's an equal loss for shareholders who have gone long.

So what can be done?

Regulators around the world have already attempted to police short selling more closely. The Securities and Exchange Commission in the US, for example, has prosecuted traders for spreading false rumours about companies they've sold short. The Financial Services Authority in the UK still hopes to bring similar charges against the HBOS raiders.

New rules have also been introduced. Naked short selling is illegal in the US in most circumstances. In the UK, the FSA announced earlier this year that anyone shorting the shares of a company holding a rights issue to raise new funds would have to disclose their trading positions once they exceeded quite low thresholds. It has promised additional regulation if these rules do not prove sufficient to prevent market abuse.

Pressure has also been brought to bear on stock lenders. Many pension funds now operate on the basis that they will not loan out any of their shares. But the fact remains that short selling, when done within in the law, is a legitimate investment practice and an outright ban would be a draconian intervention. Buying shares in a company is, in essence, a simple gamble that the price of the stock will rise. Why should investors not also be allowed to bet on a fall in share prices?

Is short selling just another example of City excess?

Yes...

* Making money as companies lose their value is simply profiting from other people's misery

* Short selling is very often associated with murky – and even illegal – market practices

* Hedge funds, often owned by a small group of traders, make massive profits from driving down share prices

No...

* Betting on a share-price fall is no less legitimate an investment than gambling that the market will rise

* City regulators already police the financial markets to curb illegal practices and catch those who flout the rules

* Some instances of short selling are just a way of reducing the risk of very large "long" investments

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies