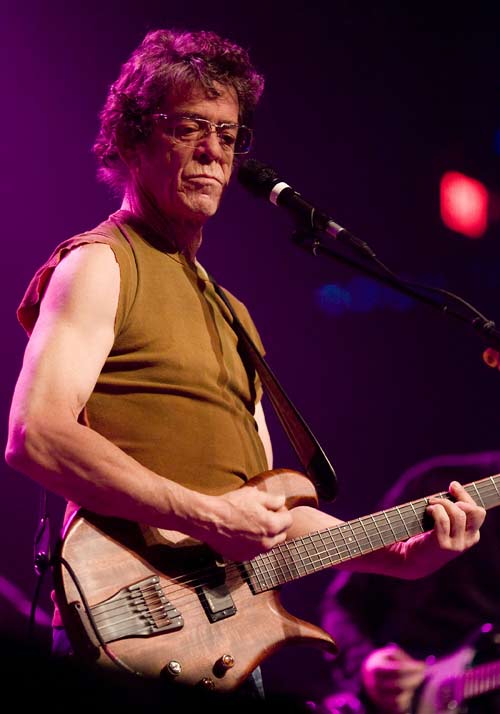

Lou Reed, Royal Albert Hall, London<br/>Beck, Guildhall, Southampton

Lou Reed's performance of his 1973 album in its entirety shows that some things are better left in the past

The last time I reviewed Lou Reed in this column, I made what I thought was a fairly transparent joke about taking heroin in the toilets beforehand. The credulous media diarist at The Guardian took this at face value, and alerted that newspaper's entire readership to my apparent junkiedom. This time, then, with a face as solemn as Reed's, I shall report that I watch Lou Reed recreate his entire Berlin album fortified by nothing other than a small bottle of overpriced cider.

But if ever there was a time to numb out and make the hours pass painlessly, it's when Lou Reed is in the mood to impress upon us that he is a Serious Artist, who wears wire-rimmed glasses and everything.

Berlin is a curious album to be giving the "recital of a masterpiece" treatment. Particularly in the UK, where it was his previous album, Transformer, that had the bigger impact: partly due to catching the post-Bowie gender-bending zeitgeist, and partly because it was available cheaply in department stores, making it accessible to generations of student bohemians who imagined themselves to be Burroughsian transgressives when they were actually Richard Beckinsale in Rising Damp.

Personally, then, I come to Berlin fresh, unencumbered by preconceptions. Released in 1973, Berlin turns out to be something of a concept album, nominally set in the German capital, centring on the tragic life of a certain Caroline as she struggles with drugs, poverty, domestic violence and child custody battles.

With typical overkill, the chimpish Reed – in his cap sleeves and skinny jeans, looking more than ever like one of the garage mechanics from the "Uptown Girl" video – chooses to present it with a seven-piece band (containing original guitarist Steve Hunter) who are themselves backed by an eight-piece orchestra (the London Metropolitan), who are in turn backed by a dozen choirgirls (the New Millennium Children's Choir, who are brilliant). In the simple mind of Lou Reed, this is how you signify Art with a capital A.

Which it isn't, really. Listen to Reed's former bandmate John Cale's work from the same era (specifically Paris 1919, released a year after Berlin) and weep at the gulf in class. It wasn't until 1989 that, in New York, Lou Reed made the album Berlin thinks it is.

Nevertheless, it's filled the Royal Albert Hall with fans who have long since swapped their Raybans for bifocals, and who have in many cases brought their children along (which surely counts as some sort of abuse).

The narrative is brought to life by a film show which depicts ordinary people having fun and having fights, or scenes acted out by a Debbie Harry lookalike, projected on to a chinoiserie screen whose relevance is obscure, unless it's a nod to the quantity of Chinese rocks consumed during the album's recording.

None of which can mask the sheer awfulness of Reed's lyrics, which recall both Baldrick's poetry in Blackadder Goes Forth and that of the Vogons in The Hitch-Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy. Sure, I'll give him "You can hit me all you want to/But I don't love you any more", but rhyming "vile" with "vial" deserves a slap. The album ends with a sad song. It's called "Sad Song". It goes "sad song, sad song, sad song ..." for what seems like a quarter of an hour. How does he come up with this stuff?

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

He encores with an extended, semi-comical "Satellite of Love", "Rock and Roll" and "The Power of the Heart", the song he wrote for a Cartier watches campaign. Which is about as far from the message of Berlin as one can get.

I've had two near-misses with the Church of Scientology. The first was when I was a student, and was lured into its Tottenham Court Road branch for a personality test. I was told that I was a borderline psychopath and potential serial killer. Being a student and a goth, I thought this was pretty cool.

The second time, in Los Angeles, I wandered into their open-access cinema, which appeared to be unmanned and deserted, and sat down to watch a film about dianetics. Five minutes in, I sensed shadowy figures moving around my peripheral vision, and ran for my life.

Beck Hansen had no chance of escape. Old Father Hubbard's crew had him from childhood, and he, like John Travolta and Tom Cruise, is one of those celebs who, one is disappointed to learn, doesn't see anything crazy about Earth being colonised 75 million years ago by an alien dictator called Xenu.

Oh well. So the happy-go-lucky purveyor of slacker rap and backpacker beats ain't so groovy after all. But he's doing a fine job of hiding it. Beck's current tour is a textbook lesson in how to win over a crowd. For his opening salvo, he wheels out the hits, to remind us who he is and what he does . "The Devil's Haircut" is the opener, followed by "Nausea" and "The New Pollution". Not long after, Hansen, his lank locks and plaid shirt belonging to an age where Kurt hasn't died, straps on a guitar, plays some bottleneck blues and – surely not! – launches into "Loser". This, as far as I can make out, is only a little less likely than Radiohead playing "Creep", and it raises the roof.

One way to soften up an audience. Now he says he wants to play "a few new songs", and is actually applauded for it. The disastrous Sea Change, the turgid 2002 album recorded shortly after he'd been dumped by his girlfriend (one of the worst cases of an artist Going Serious in recent history) is just a bad memory now. The material from current album Modern Guilt is vibrant, drawing on freakbeat and R&B (Sixties sense). And it doesn't outstay its welcome: a cover of the Korgis' "Everybody's Got to Learn Sometimes" is a pleasant surprise, and "Where It's At" a crowd-pleasing finale. Only the addition of "Sexx Laws" would have made this the perfect Beck gig.

Need to know

Born in 1942 into a Jewish family in Brooklyn, the teenage Lou Reed was subjected to electroconvulsive therapy to "cure" his homosexuality. He worked as a house songwriter for Pickwick Records before finding cult fame with art-rock band The Velvet Underground. Post-VU, he released a succession of acclaimed albums, most significantly 1972's 'Transformer', whose themes of drug use and cross-dressing chimed with the mood of the glam-rock movement spearheaded by his friend David Bowie.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies