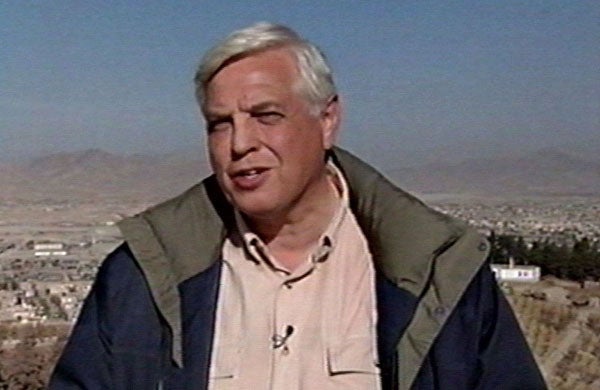

Unreliable Sources, By John Simpson

The abiding image of John Simpson, the BBC's weighty World Affairs Editor, is of him attempting to do a Max Hastings and lead the liberation of Kabul in 2002, all crouching caution and whispered remarks back to the camera, only to meet the BBC's local correspondent - who had been reporting from the city throughout the war. Hastings has since recanted of his self-promoting dash to precede the troops into Port Stanley in the Falklands war. Simpson doesn't mention his Afghan venture in his latest book, although he gives high praise to Hastings for his act.

Embattled and under-resourced today's reporter may be, but it still remains the most glamorous of jobs if you can get in front of a natural disaster, a war or a ministerial resignation, with a camera at the ready. Not that you would know it from Simpson's book which sets out to record "how the 20th century was reported". It's a hefty near-600 pages, much of it clippings dutifully provided by an assistant during his travels. Readably, it trots through the major events of the last century as seen through the eyes of British journalists from the Boer War to the invasion of Iraq.

But it's an oddly dispassionate book, as if Simpson were not himself a reporter with experience to contribute to this history of his trade. Even in describing the infamous Andrew Gilligan report on the Today programme and its consequence in the Hutton report on Iraq and after, he stands aside as if above it all. Simpson himself, indeed, only really appears once, when he repeats a tirade by Tony Blair against a BBC man, whom he then coyly adds in parenthesis "was in fact the author of this book".

The occasion of the outburst was the British government's anger at the way that Simpson was reporting NATO's air assault on Serbia over its actions in Kosovo. The BBC was suggesting that the bombing was neither as accurate as the allies claimed nor as effective in turning the population against their leader, Slobodan Milosevic. Ministers felt the BBC's even-handedness was "unhelpful"; some of the popular press regarded as downright treasonable with British forces in action.

If the book has a theme, it is that – the story of good, honest reporters trying to record events as they saw them against military censors, government press officers and overweening proprietors determined that they should not. Simpson is surely right, if hardly novel, in saying that there has always been a tension between straight reporting and the interests of authority and, indeed, populism.

But to write the history in these terms rather misses the point. Journalism isn't some academic exercise nor reporting a craft of neutral observation. The media have always been part of life and politics, the instrument of events as much as their influencer, and the journalists inspired far more by the spirit of competition with one another than some higher calling of "truth."

In that sense Simpson – of all people – should know that ego is the mainspring of a large part of the best journalism, particularly abroad. The stories that move people, from William Howard Russell's devastating exposures of conditions in the Crimean war, to the BBC's reports of famine in Ethiopia and the killings in Darfur, are those composed with the desire to "affect" their audience and bring their authors fame. The consequences may be beneficial, the balance is often missing.

The problem of reporters today is not the pressure from above to tailor their stories to the beliefs of the paper or the whims of their proprietors or, indeed, the influence of ministers. Those have always been there. The difficulties – the decline if you want to call it that – of good journalism are reflections of the travails of the media itself: the lack of resources for reporting, the rise of the blog and mobile phone as the main sources of on-the-spot information, the dramatic reduction in the number of specialist journalists and the diminution of the role of the interpretative reporter – of which Simpson's own recent career is part. Comment is free but facts are expensive, as the saying of modern journalism goes.

A century ago the reporter from Britain could bestride the world as a media star visiting faraway places and obscure battles as if of right. Today he daren't venture out of the Green Zone of Iraq or the capital of Afghanistan. His place is being taken by local reporters facing far greater dangers for far less return than the princes of Fleet Street and the BBC of yesteryear. To that extent Simpson's book is what he would have journalism be – dispassionate, accurate but without life.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies