The eternal curse of rock histories is their earnestness. Every incident is weighted with wearying significance, because if the author doesn't take his subject seriously, who will?

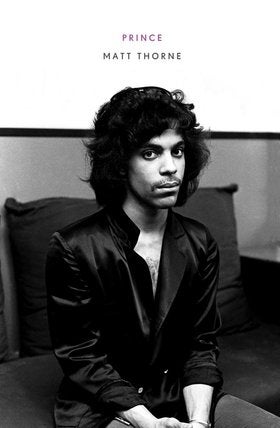

One hopes the novelist Matt Thorne will take a different approach. He has a great subject. Prince Rogers Nelson is fascinating, the sort of rock star an author might invent. He writes songs in and out of character, and across genders and sometimes specifically about his public persona. His best-known band, the Revolution, was mixed in race, gender and sexuality, nearly 30 years ago. His headquarters, the purpose-built Paisley Park in Minneapolis, is part factory, part fortress, yet he sometimes invites fans in. He changed his already unlikely birth name to a glyph to escape a record deal. (Others hire lawyers.)

And beyond the seemingly eternal public performance there is a private life. He lost a severely handicapped newborn son. Wildly driven, it's unclear if he ever had time for the interesting sexual practices he's so often described. He's a vegan, a Jehovah's Witness, a dreadful filmmaker, a keen basketballer (despite being five foot one) and, these days, berates his audience for swearing and fornicating, the sexy motherfunker.

Unfortunately, Thorne is a Prince fanatic, once considered for the job of approved biographer. A conventional life story wasn't expected, but this doorstop amounts to a speculative description of every song Prince has recorded – especially the unreleased ones. It is packed with adoring speculation. Every detail, no matter how trivial, is "interesting" or "fascinating". Tedious descriptions of obscure movies and bewildering explanations of the plotlines of forgotten albums take up hundreds of pages.

Prince probably warrants the song-by-song approach, but Thorne is no Ian MacDonald, trained in musical theory, and soon runs out of vocabulary. Any tune that swings with a I-IV-V change is dismissed as "rockabilly", while his use of "hard rock", to describe a guitarist often compared to Hendrix, is extraordinarily vague. Thorne's research into Prince's protégés is impressive, but of relatively limited interest, while his subject's drift into bigotry is barely questioned. In fact, Prince's religious journey is hardly mentioned, despite teasers.

The absence of lyrical quotes, presumably for legal reasons, is a hindrance for the author (and reader), especially when Thorne prefers to work backwards from the lyrics – never the most reliable way of tracking down the artist. And a wider engagement with the world beyond is lacking. The odd incisive quote – such as his former publicist's assertion that Prince is "terrified of men", or Andy Warhol's diary comments about his bad dancing – is refreshingly non-consensual. But for all we know, The Benny Hill Show was a crucial influence on Prince's strip club aesthetic – he's played the theme tune on stage. Prince is not boring, but this book is, extraordinarily so.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies