Boyd Tonkin: Kindling our debts to the digital elite

The Week In Books

Remember videos? Chunkily packaged to look like books, these plastic cases filled with tape first gave us the idea that films and TV shows could be acquired for enjoyment at will. Often, especially with children's favourites, the ad campaigns would draw on phrases such as "Yours to keep for ever". At the time, that sounded awesome. Yes, you really could buy and store audio-visual entertainment, just as with a book.

Videos went the way of all perishable kit, but time and technology have blown in a very strange reversal. Now, millions of PR dollars try to persuade us to forsake print-on-paper books. Instead, those nice guys at Amazon and Google will let us browse or withdraw titles from their vast virtual libraries - whose standards, rules and fees may change on their whim at any time.

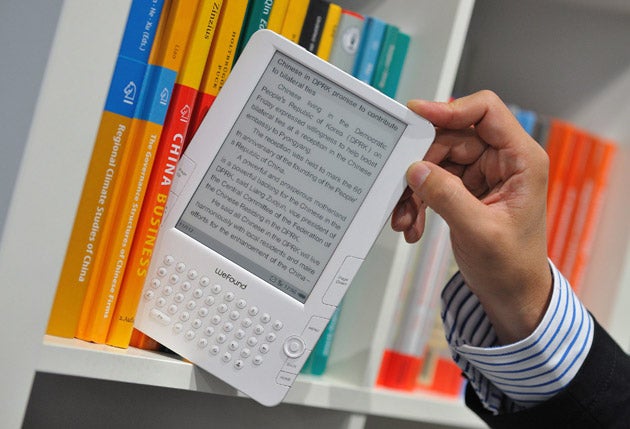

From Monday, Amazon will ship its Kindle electronic reader to non-American customers, offering around 200,000 books via the 3G wireless network but - compared to the US - at a premium price. In Britain, the imported device (at around £175) will join a market crowded with competitors such as the Sony e-reader. Besides, Apple is currently cooking up its "Kindle-killer" tablet-style gizmo as a deadly riposte.

In another part of the electronic wood, Google's plans to digitise libraries and publishers' lists still face tough challenges in the courts of Europe and America. German Chancellor Angela Merkel weighed in with her doubts about the ambitions of the Google Book Search project prior to this week's Frankfurt Book Fair. An urgent worry is Google's claim to take sole charge of storage and distribution of "orphaned" works with no clear copyright holder.

Open access to reading for ordinary people has partnered the struggle for liberty throughout the world. It is, by the way, a principal theme of Hilary Mantel's Man Booker winner Wolf Hall, in which Thomas Cromwell advocates the right to own and study the vernacular Bible against Thomas More's view that collective control should prevail. But why raise these lofty antecedents in relation to marketplace or courtroom scraps over how many books we can read for free online (Google), or how much we pay to plug into titles from a virtual store (Amazon)?

The answer should be obvious. Google began its breathtaking rights grab over the digital word by assuring us that "we are not evil". This is about trust; more specifically, about the prudence of handing over the keys to the online library to a tiny handful of corporations. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos had to grovel when it deleted – of all novels – Orwell's Nineteeen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm from Kindles after a screw-up over licences. That debacle served to warn of the risks of outsourcing delivery of books to foreign entities over whose actions we have no say.

A company is a company. A boardroom coup or a stockmarket slide can change its colours in a trice. Why should Google or Amazon act differently? House your personal library on the servers of the West Coast or the ever-changing hardware that hooks you up with them, and you take a gigantic gamble on the future probity of those who can turn the taps of culture on or off.

Questions of cost and copyright aside, we have no guarantee that remote harvesters and processors of electronic texts will not fall into the hands of censors or bigots. The arguments against over-mighty monoliths in old-style print publishing sound even louder in the digital domain. And we have lately had experience of profit-driven giants who for long years behaved with customers as if they shared a notion of the common good: high-street banks. But they put on two faces, spoke with two voices, and in the end swooned into the arms of the state when a crisis unmasked their hypocrisy. If, at some stage, Google or Amazon go bad or go bust, few people will forfeit life savings. But if we place as much blind faith in them as they now demand, how much cultural capital do we stand to lose?

P.S.Herta Müller - aka Herta Who? in much of the perenially baffled US media - has in fact had more of her work translated and published in the Anglosphere than several other winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature. As with every author from outside the English language who catches the Swedish limelight, a dedicated offstage team merits applause. In her case, that includes the eagle-eyed Pete Ayrton of Serpent's Tail (which published Müller's The Passport, and re-issues it this month), Margaret Halton – now an agent – who acquired the IMPAC Prize-winning novel The Land of Green Plums for Granta, and of course Müller's translators. On this side of the Atlantic they include Martin Chalmers and Michael Hofmann, two of the most gifted and versatile carriers of modern German writing into English. Glückwünsche all round.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies