Fiona Banner: Wp Wp Wp, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield, review: Blown away by an awesome air show

The helicopter blades which spin from the ceiling are a display of might – their size and proximity overwhelms viewers who stand with their faces turned upwards, as blades slice the air like knives above them

Artist Fiona Banner’s fascination with military aircraft goes back a long way.

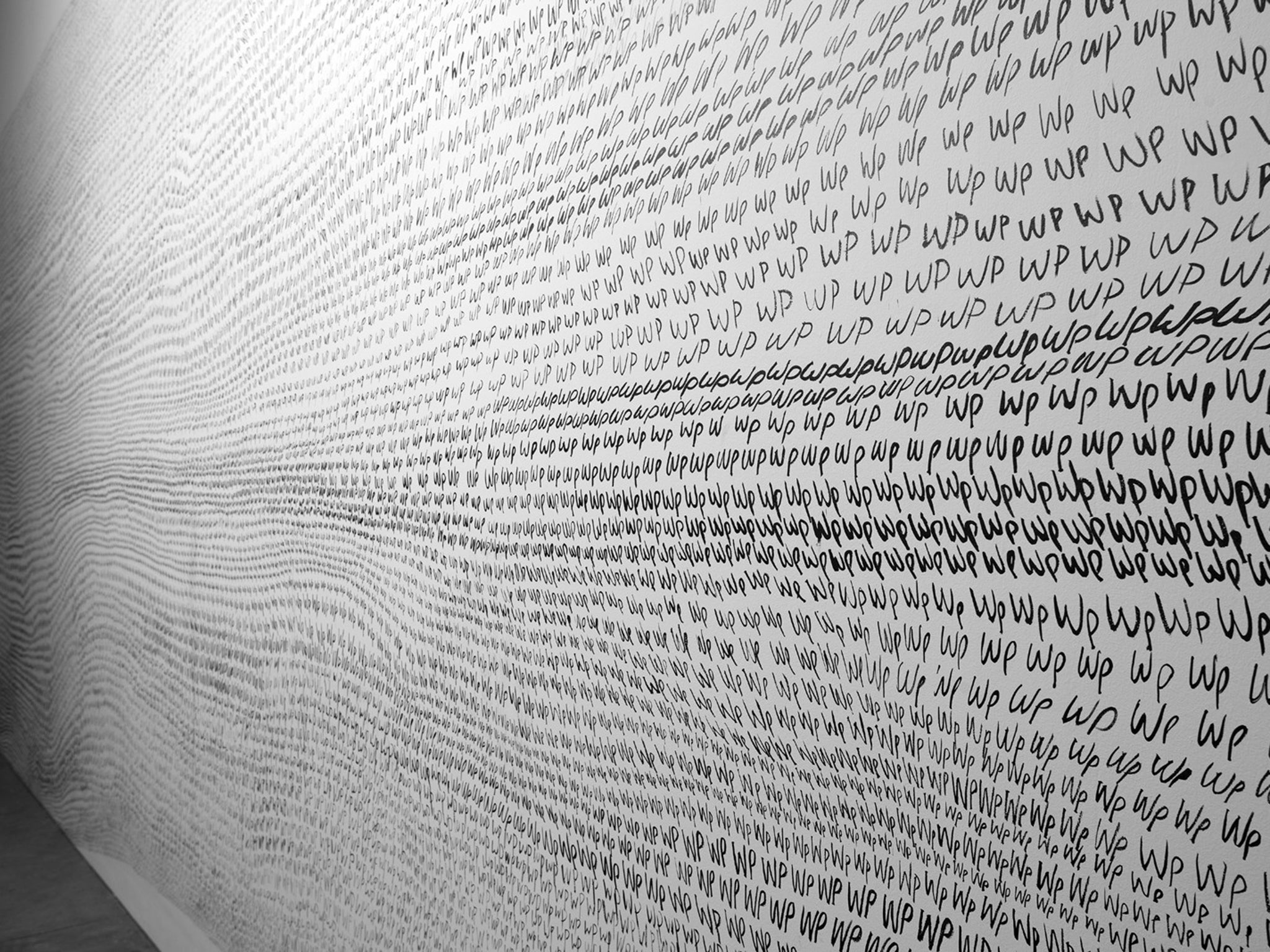

From childhood walks with her dad when fighter jets ripped through the Welsh valley, she first experienced a sense of excitement and fear that has stayed with her since. She watched war films as a young woman, and for an early artwork called The Nam she wrote out the entire action of Full Metal Jacket, The Deerhunter, Apocalypse Now, Platoon, Hamburger Hill and Born on the Fourth of July. In the 1,000 pages of text, a helicopter sound appears as wpwpwp. This forms the title of her latest exhibition Wpwpwp at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

In the gallery, a pair of military helicopter blades spin from the ceiling. They’re configured to rotate in opposite directions, like a Chinook helicopter – used in Vietnam and still in service today. It’s a display of might – their size and proximity overwhelms viewers who stand with their faces turned upwards, as blades slice the air like knives above them. I’m frightened they might crash, or cut a person in half. Like in Harrier and Jaguar – she strung a decommissioned Sea Harrier from the ceiling of Tate Britain where it hung like a dead pterodactyl – this piece of aircraft creates an odd and compelling aesthetic.

Contradictions swirl like the blades around the room. Banner’s childhood emotions are here: excitement and terror, revulsion and admiration. To stand beneath it feels potent, uncomfortable. A display of power, which usually remains distant and detached is brought up close and intimate. It’s criticised, and yet there’s a sense of awe and wonderment too.

A series of different-shaped holes make windows in darkened glass along the gallery’s front. It’s a row of full stops in various fonts: Times New Roman, one splodge is from the Peanuts cartoon. They’re a pause, a breath, when nothing is said. Their view is out over a ha-ha into pristine Yorkshire landscape, they float above cattle, stone walls, a lake in the distance. It’s a play on sculpture in a landscape, which is man-made and not as organic as it appears – and a slight dig at hubris, of giant bronzes in the park.

Intermission is a filmic version of the full stops, the space in between. For Banner it’s a moment when she couldn’t find what she wanted to say, and struggled to make anything. There’s pathos in her films. Tête à Tête shows two mechanically operated windsocks act out a romance as they blow to each other through the trees.

In Mirror, the actress Samantha Morton reads the artist’s nude portrait of her, rendered in word not image. “Wide hips stretching her baby fucked stomach,” she says. Through language we imagine her naked body as she reveals it to us, it’s unflattering, raw. Morton falters, embarrassed before the crowd. It’s a brave performance, an exploration of nude portraiture’s history.

War poets who are women have written about war from home, of absence, trauma and death. There’s lyricism within Banner’s work, poetic form in the rhythm of the helicopters’ blades, in her use of language, intermissions and full stop.

To 4 January (01924 832631)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies