What I've learnt as a performer is that even the politically 'woke' still get embarrassed by the idea of disability

When a member of the audience clearly has Tourette's or a similar condition, the sympathies of theatre-goers can still unfortunately wear thin – but access to culture is so important for us all

I recently read an article about an actor whose non-verbal and severely physically disabled son was forced to leave the theatre where his father was performing, because the audience couldn’t cope with the boy’s “noises”.

As a human being, I felt incensed on behalf of both the child and his dad, but as a performer and audience member – if I’m totally honest – I also felt a teeny bit of sympathy for the old biddy who did the “shushing”, resulting in the boy having to leave the theatre.

Not much, I grant you, but a tad.

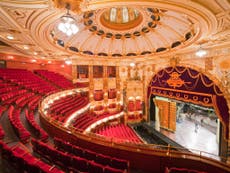

Morally, the biddy was in the wrong: we are all chasing a fairer, more inclusive future, and if that means sharing an auditorium with people who have been dealt a pretty tough hand in life, then I think we should all suck it up. I sympathise because she presumably had no idea that the boy in question was disabled, and assumed instead that he was a teenage troublemaker. If you’ve paid 90 quid for a West End seat, someone making “funny noises” behind you, seemingly deliberately, is irritating. Few take the time to consider in their day-to-day lives that that person might be suffering from a disability rather than an urge to disturb people around them.

Sadly, the profoundly disabled continue to sometimes leave even those who consider themselves politically woke feeling “embarrassed”. I really wish it wasn’t the case, but it is. And we need to talk about this uncomfortable truth.

We are all pretty intolerant of noise where we don’t want or expect it: we rail against the kid with the garage music leaking from his headphones in the quiet carriage of a train, or the party in the nextdoor hotel room kicking off after midnight when you’re trying to sleep – but do we have a right to complain in very different cases like these, when the result could be that a disabled person is denied access to culture?

I remember going to see a play in the West End and the woman next to me was wearing what I believe was a hearing loop, which seemed to amplify the sound of the performance via her hearing aid. I’m not sure what the situation was, but unfortunately, the thing seemed go in and out of frequency and at times it was like sitting next to a badly tuned transistor.

But you know what? I’m pretty hard of hearing myself – and who knows, in 20 years’ time I could well be in the same situation. I shut my trap and put my scarf over the ear that was closest to her.

I’m bringing this story up now because during a recent Grumpy Old Women gig, a member of our Reading audience began making “noises”. Instantly I knew they weren’t drunk women shrieks – this was either Tourette’s or a similar disability.

It actually didn’t bother me. I know the show well enough not to be put off my stride, but I could sense a tension in the crowd; a palpable feeling of: “Oh no, oh God, what’s going to happen next?”

Not much, as it happens. The person made a few more noises, but I like to think they were sounds of enjoyment. The next thing I knew, it was the interval.

Of our cast of three, one admitted to being slightly thrown; the other two, having come up through the ranks of the Eighties and Nineties stand-up and cabaret circuit, had experienced much more difficult interruptions.

In my twenties, I was unceremoniously “hummed” off stage at the Tunnel Club, when the infamous compere Malcolm Hardy enforced a heckling ban. The Tunnel Club was notorious for heckling, but that night Malcolm only had five performers booked and within 20 minutes, three had already been booed off. I was next up.

I tell you, the sound of 300 people humming me off stage and back to the dressing room, tail between my legs, is something that haunts me to this day.

But that’s beside the point. The answer to true theatre accessibility (apart from lowering ticket prices, which is the biggest barrier that we all face) is to hold “relaxed” performances where all people can enjoy performances without fear of disapproval.

Many smaller theatre spaces around the country do offer these special nights. I remember going to see a show my daughter had written a couple of years ago – it was a monologue, and the actor had invited a friend with Tourette’s.

This turned out to be the performer Jess Thom, who was diagnosed with the neurological condition in her early twenties. Throughout the 60-minute show, Jess shouted the words “biscuit” and “hedgehog” at frequent intervals.

I have to admit, I tensed up a bit. The young hipster audience, on the other hand, barely batted an eyelid; they knew what was going on and they could cope.

We are getting better, people are more educated, but it’s not all plain sailing. When we got back onstage in Reading after the interval, our “noisy” audience member had gone.

In some respects, I hope they left because they hated it, rather than because they were made to feel uncomfortable and unwanted.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies