Stargazing in October: Watching Greek myth play out in the constellations

The legend of Perseus and Andromeda tells of sea monsters and women with snakes for hair, and the story is in the skies this month

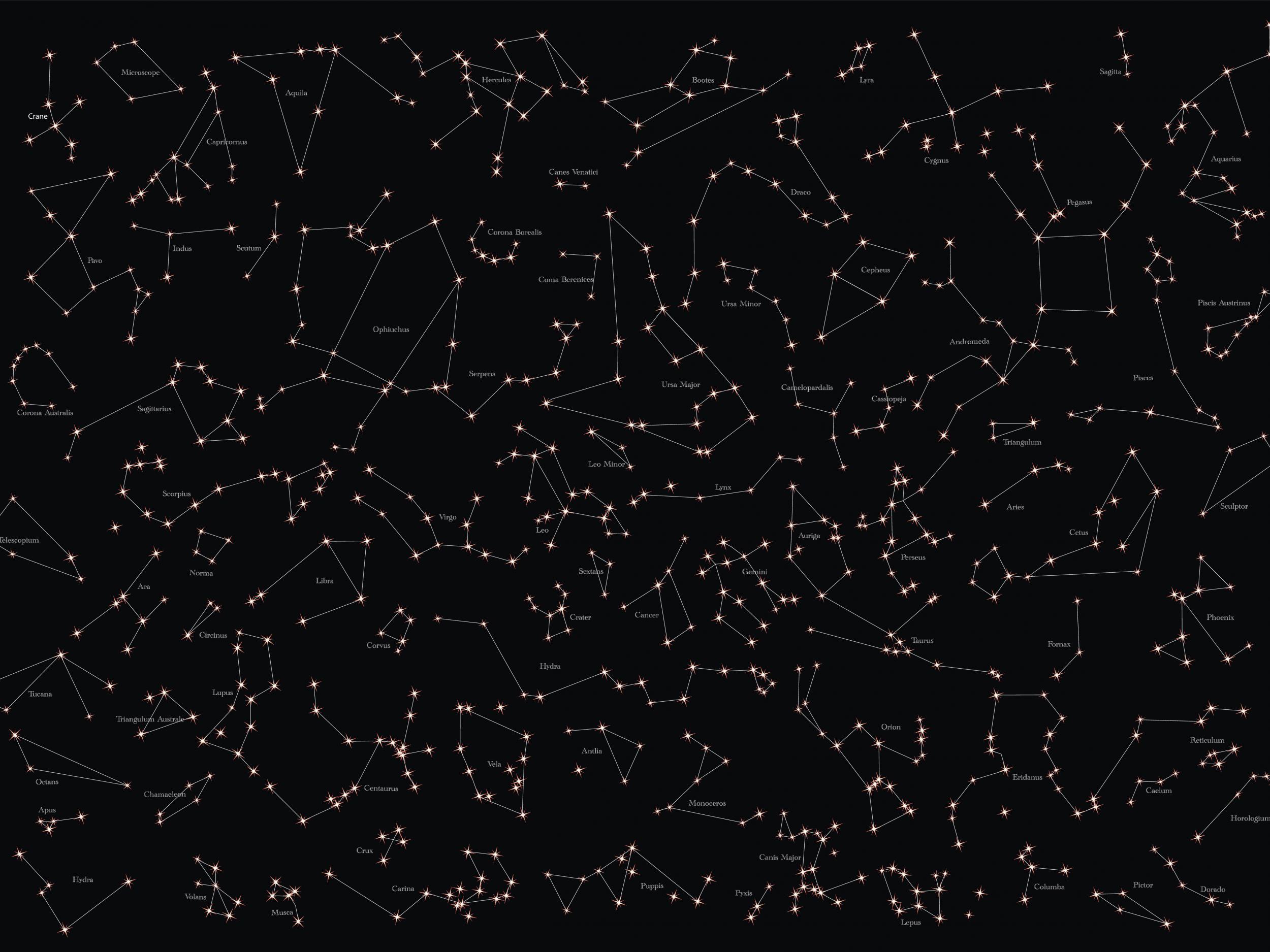

Wedged between the softly shining stars of summer, and the dazzling denizens of the winter sky, autumn’s stars come off badly. The heavens look tired and dull; there are few really bright stars, and the constellations look – frankly – boring. Can you see an upside-down flying horse in a barren square of stars (that’s Pegasus, by the way)?

But you have to hand it to our ancestors – and to the Greeks in particular. They pinned their myths and legends onto the sky as aide-memoires to recognising the constellations. Never mind if Pegasus didn’t look like a horse; Greek navigators at sea, and farmers on land, would connect the constellation to their time and place.

The Greek myths are a veritable orgy of lust, power and manipulation. If you think modern politics is convoluted in the extreme, try reading Robert Graves’ The Greek Myths. Nothing changes!

What the autumn skies lack in beauty, they make up for in story-making – played out by constellations that are well on view this month. This is the legend of Perseus and Andromeda. To find Andromeda, go back to Pegasus. You’ll spot a line of faint stars at its left-hand end. It takes enormous imagination to see these stars as a maiden chained to a rock – about to be gobbled up by a sea monster – but there it is.

How did she get there? Her mother Cassiopeia, the Queen of Ethiopia, boasted to the sea-god Poseidon that Andromeda was more beautiful than all the sea-nymphs. Oops, not a good move. The enraged god sent a sea-monster (the constellation Cetus) to ravage the kingdom. Every night Cassiopeia (a bright W-shaped constellation) and her husband Cepheus (faint and kite-shaped in the sky) had to sacrifice a youngster to the behemoth.

Night sky: North east landmarks captured under celestial light

Show all 12But it wasn’t enough for Poseidon: he wanted Andromeda. That’s how she ended up on the sacrificial rock, with the ravening Cetus bearing down on her.

Enter Perseus (a bright and interesting constellation visible all year round). In myth, he was the son of beautiful Danae and the god Zeus (who had had his wicked way with her). The local king had his eye on Danae, but young Perseus knew that the man’s intentions were not honourable. So the king banished him to one of the furthest corners of the Earth with the instruction: Kill Medusa, the Gorgon.

The three gorgons were sisters, with snakes for hair, and a gaze that would turn an onlooker to stone (ever had a teacher like that?). Two were immortal; but not Medusa.

Perseus planned his campaign carefully. He would have to be invisible; need winged sandals in order to fly; and have a reflective shield to point at Medusa’s face, so as not to look at it directly. It all came off – Medusa was killed; and the drops of her blood spilled out to form Pegasus. But on his way back, Perseus encountered another challenge: a beautiful maiden about to become a sea-monster’s dinner. He swooped, and beheaded the snarling Cetus with one stroke.

Nothing for it but to marry and live happily ever after? But Perseus had an extra obstacle to face. Andromeda’s scheming mum, Cassiopeia, had lined up a more suitable suitor for her daughter – and he burst into the wedding ceremony accompanied by 200 supporters. Perseus put up a good struggle, but then it was his lightbulb moment. He grabbed Medusa’s head, and – hey presto! – the whole gang turned to stone. The moral? Even gorgons have their uses.

What’s up

Overhead and to the south, you’ll find the constellations of the Andromeda legend, as featured in our main story. They’re framed to the west by a brilliant trio of stars – Vega, Deneb and Altair – and to the east by the rising stars of winter, headed by Capella and Aldebaran.

Look low to the south-west in the early evening for some planetary action: brilliant Jupiter setting around 9pm, and – to its left – fainter Saturn slipping below the horizon two hours later. Right at the end of the month, they’re joined by brilliant Venus, very low down just after sunset. If you look to the lower left of Venus (best with binoculars) you may catch elusive Mercury, too.

In the meantime, watch out for shooting stars. This month, the Earth runs into specks of dust shed by Halley’s Comet, which burn up in the atmosphere as fast-moving meteors. This particular shower, the Orionids, reaches a peak on the night of 21-22 October, but you may catch some for a couple of days around that date.

Diary

3 October: Moon near Jupiter

5 October, 5.47 pm: Moon at First Quarter, near Saturn

13 October, 10.08 pm: Full moon

17 October: Moon in the Hyades star cluster, near Aldebaran

20 October: Mercury at greatest eastern elongation; moon near Castor and

21 October, 1.39 pm: Moon at Last Quarter; maximum of Orionid meteor shower

22 October, 4 - 6 am: Moon occults the Praesepe star cluster

27 October, 2 am: British Summer Time ends

28 October, 3.38 am: New moon; Uranus at opposition

29 October: Crescent moon very near Venus

29 October: Crescent moon between Venus and Jupiter

31 October: Crescent moon very near Jupiter

Philip’s 2020 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky next year.

Fully illustrated, Heather and Nigel’s The Universe Explained (Firefly, £16.99) is packed with 185 of the questions that people ask about the Cosmos.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies