The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Nicholas Coleridge interview: ‘Influencers just don’t have the depth of knowledge that great fashion journalists do’

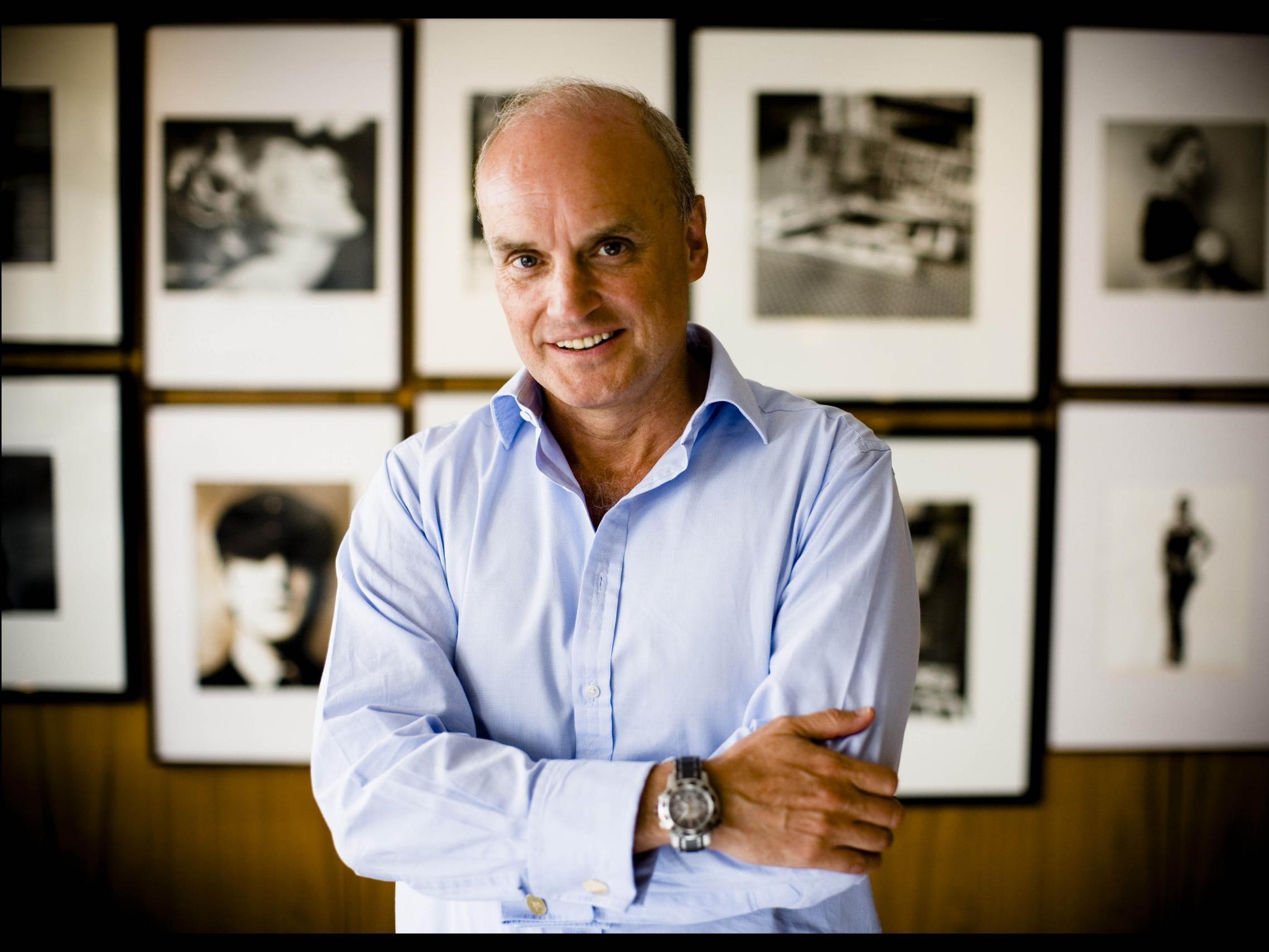

Olivia Petter sits down with the magazine mogul to talk social media, the future of Vogue – and Princess Diana’s breasts

Nicholas Coleridge is despairing over fashion influencers. “They can be very valuable to brands, but I don’t totally approve,” the chairman of publishing house Condé Nast Britain tells me, reclining in an armchair in his lovely Chelsea home. “Great fashion journalists have a depth of knowledge and are able to make judgements that are useful and meaningful. Influencers have large followings and are invited to fashion shows where they’re photographed with a terribly nice new handbag given to them by a luxury label. I don’t think it’s journalism.”

Coleridge’s view is not unusual. In 2016, US Vogue’s Sally Singer caused a ruckus for expressing a similar view, writing that “bloggers who change head-to-toe, paid-to-wear outfits every hour” are “heralding the death of style”. Needless to say, influencers view their role in the industry rather differently.

Peter Lindbergh's best Vogue covers

Show all 10Coleridge is a character. He rattles off tales about his life and circle of high society friends with theatrical charm, his voice clipped and sonorous. Ricocheting from one anecdote to the next, he frequently changes the way he sits to act out scenarios. So voluble is he, in fact, that it can be difficult to get a word in edgeways. It might be frustrating were he not so warm and hospitable: I am offered tea several times and his wife, Georgia, pops in to check if I need anything else.

We’re here to talk about Coleridge’s new memoir, The Glossy Years, which charts the 62-year-old's mammoth career, from Tina Brown protégé to managing director at the publishers of Vogue and GQ, Condé Nast, where he worked for nearly three decades (he stepped down from his managerial roles two years ago, but remains chairman until the end of this year). In 2015, Coleridge was appointed chairman of the Victoria & Albert Museum, having previously been chairman of the British Fashion Council (BFC) and the Professional Publishers’ Association (PPA). In between, he somehow managed to write 12 books, but his latest – and most personal – is the most scintillating of them all.

“Are you trying to f***ing poison me?” Coleridge recalls Philip Green saying when being served wine at a GQ dinner

Coleridge’s world glitters to the point of satire, something of which he is acutely aware. Childhood friends have names like Trelawny or Rupert (he went to Eton), and come from families that own islands, while today’s network comprises Lords, heiresses and CEOs. But despite his well-to-do upbringing, Coleridge projects himself as an observer, noting and mocking the social nuance of the privileged inner circle within which he operates.

Readers have Coleridge’s astute observational skills to thank for the series of lively anecdotes that fill his memoir. There’s the time he says Philip Green almost gagged from wine served to him at a GQ dinner (“Are you trying to f***ing poison me?”), so bought a £3,000 vintage bottle of claret instead. Or the time he gets arrested in Sri Lanka as a young journalist, only for it to make headlines back home in the UK, prompting his father to bail him out and the police chief to say that Coleridge "must come back soon for a holiday". And a recollection that sounds as though it has been pinched from the pages of an Oscar Wilde play: the moment Coleridge says he resolved a very serious lawsuit with Harrods’ PR chief Michael Cole while the pair were naked in a Mayfair steam room.

“I wanted to touch on the funny stuff,” Coleridge explains of writing the memoir, revealing he had initially been apprehensive because “it might seem a bit vain”. Sure, the namedropping (Kate Moss, Rupert Everett and Elizabeth Hurley all receive mentions) verges on self-aggrandising, but then that was the world he lived in: Coleridge climbed the ranks in magazines during their Eighties heyday. The parties were opulent, the advertising budgets unlimited.

Princess Diana would sometimes pop into his office at Vogue House, and on one particularly memorable occasion, Coleridge writes, asked if he thought her breasts were “too small”. A tabloid newspaper had just published photographs of the late royal sunbathing topless on a balcony in Spain. “It was oddly striking because I didn’t know her particularly well,” Coleridge recalls. “She was quite mercurial. Sort of flirtatious too.” Diana’s attendance that day was strictly confidential. And yet a crowd of photographers were waiting for her outside because she’d alerted the press herself, as Coleridge later discovered. “People get very used to being in the public eye, so I expect she was feeling a bit insecure at that point in her life,” he explains. “I think she knew what she was doing.”

I certainly don’t think London Fashion Week should be cancelled, but we need to wean ourselves off cheap synthetic clothes

Today, when titles such as Marie Claire, Glamour and InStyle have all abandoned monthly print models in the UK, the magazine industry is not the sparkling force it once was. “The middle market has pretty much gone now,” Coleridge says. “I used to walk up and down train carriages to see what people were reading. Half had newspapers, the other half magazines.” He often counted how many people were reading Marie Claire and Cosmopolitan compared to Glamour, a Condé Nast title that became biannual in 2017. “Now I go on trains and everyone is holding their phones, scrolling through Facebook and waiting for emojis.” Social media is the reason so many middle-market titles have collapsed, he explains, “because their content was more easily replicable on other platforms”.

But it’s different at the upper end of the market, Coleridge says, citing Vogue, House & Garden and Tatler as titles with an “exclusive eye” whose authority he thinks will survive the digital apocalypse. “I think most of the top glossies will outlive me.” Coleridge’s time at Condé Nast was not without controversy. In 2017, Naomi Campbell posted a photograph on Instagram of the British Vogue staff as it was under Alexandra Shulman’s editorship. Every face in the photo was white. “Looking forward to an inclusive and diverse staff now that @edward_enninful is the editor,” Campbell wrote, rejoicing in the fact that Enninful, her close friend and former W creative director, had been appointed as Shulman’s successor. “I thought that was unfair of Naomi,” says Coleridge. “She’d appeared on the cover of the magazine so very many times during Alex’s time as editor, and was written about extensively too.”

Coleridge approves of Enninful, who has been praised for making the title feel more diverse with cover stars including Adwoa Aboah and Halima Aden, the first hijab-wearing high fashion model. “I think that Edward has taken the magazine in a slightly different direction, though he’s kept the standards high. I think he’s very good,” Coleridge says, pausing to contemplate Vogue’s new direction. He continues: “For some groups the magazine has become more for them. Against that, there will be other groups for whom it might be a little less relevant.” Another pause. “My overall view is that Alex had one of the most successful periods of editing Vogue and I think Edward is a very good person to be editing it now.”

I feel Brexit has been a terrific waste of the last three years

Today, Coleridge is much less involved in Condé Nast than he was, having passed his key duties onto others and traded magazines for museums. Snippets of glitz remain, like exhibition openings and the occasional foray to the front row at London Fashion Week. Though the latter could soon come to an end, given how much pressure the British Fashion Council (BFC) is under to address the industry’s carbon footprint. “I certainly don’t think London Fashion Week should be cancelled,” he booms when I ask what he makes of Extinction Rebellion’s demands that the bi-annual event be replaced with a summit to address the ongoing climate crisis.

“I do think we need as a nation to wean ourselves off very cheap synthetic clothes that are worn once or twice and then chucked,” he adds, taking the opportunity to pontificate about the Campaign for Wool, another one of his chairmanships. “It’s all about trying to fight back against synthetics and plastics,” Coleridge says of the organisation he runs alongside the Prince of Wales. “Sustainability is the strongest card that the wool campaign has at the moment. You can buy a wool jacket and still be wearing it 30 years later and it’s usually still in very good nick”.

Another anxiety keeping the fashion industry – along with the rest of Britain – awake at night is, of course, Brexit. The BFC has said that leaving the EU without a deal could cost the industry £900m. Coleridge voted Remain. “I feel Brexit has been a terrific waste of the last three years,” he sighs. “It’s the only time in my life when I’ve thought this is what it might’ve been like to be alive in the English civil war.” That said, he is optimistic the government will secure some sort of deal (“Theresa May’s but with knobs on”) and that the British fashion industry will come out the other side. “In the short term, it’s bad, but I expect we’ll survive and we’ll finally be able to put this completely unenjoyable episode behind us and get on with things.”

As our interview draws to a close, the heavens open. Although his home is just a few minutes’ walk from the tube, Coleridge insists on driving me because I don’t have a jacket and I’ve “come all this way”. In fact, I’ve only travelled three stops, but I get into his car and we continue to chat about the book. Coleridge hopes I will go out of my way to say how brilliant I think it is, and I get a sense that he is genuinely unsure whether or not it will be a success. For a second, I forget that the man beside me has spent three decades working in media, written bestselling novels and is one of the most established names in journalism, fashion and museums.

I play ball and tell him how much I enjoyed the book, waving my Post-It-laden copy in his eye-line (I had pulled out the yellow stickies to identify my favourite passages, and ended up with the entire book glowing in a yellow haze). He looks surprised and thanks me. “You see, I don’t really like personal publicity,” Coleridge explains, acknowledging the oddness of his remark given he’s just written a memoir. “I just don’t love talking about myself. But if you’ve spent a year and a half writing something, it’s very nice when someone shows any interest at all. The whole thing makes me feel slightly anxious.”

The Glossy Years: Magazines, Museums and Selective Memoirs by Nicholas Coleridge is out now

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies