Bass Oddity: Why David Bowie’s ‘jungle nuttah’ D’n’B phase is worth rediscovering

Bowie was an easy target for critics when he tried an ambitious new musical direction at the age of 50, but Ed Power makes the case for ‘Earthling’ being part of the most underrated phase of his legendary career

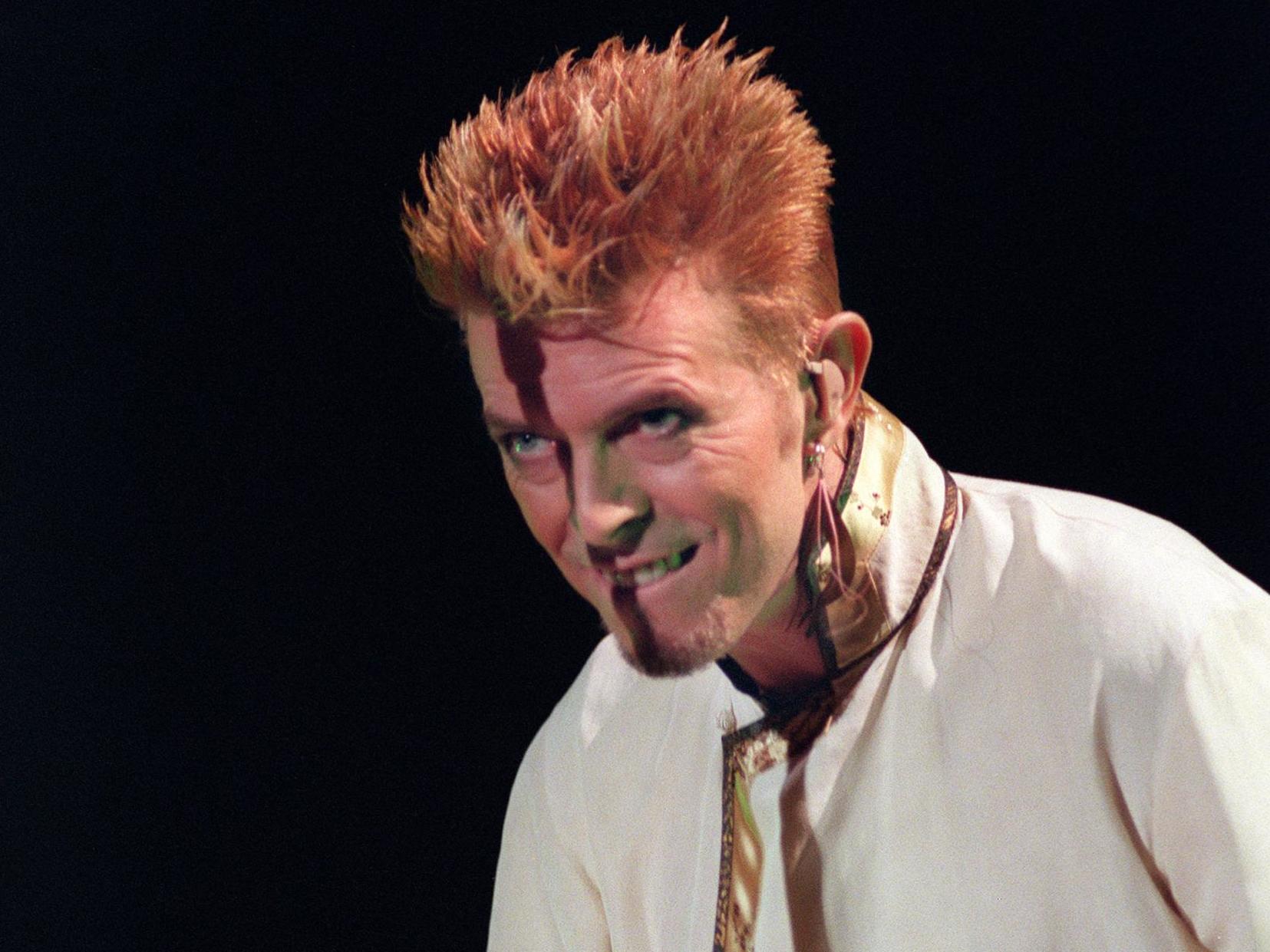

By 1997, the Thin White Duke had become pop’s flame-haired groovy dad. David Bowie was knocking on the door of 50 – ancient mariner status for rock stars of his generation. But he had no intention of joining The Rolling Stones and Eagles in their strange new endeavour of touring the world and playing their greatest hits for wodges of cash (it would never catch on). Bowie, ever the alien, was determined to proceed into his twilight years on his own inscrutable terms.

Which is why, rather than hanging out with his old mates from the Seventies, in 1997, he was more likely to be found rolling a cigarette on the steps of the 480-capacity Blue Note club at Hoxton Square, in scrappy and thoroughly unfashionable Shoreditch.

There, every Sunday night, DJ and producer Goldie curated the already quasi-legendary Metalheadz drum’n’bass night. Bowie made sure his was the first name on the guestlist. Soon pop’s greatest magpie was taking the obvious next step by setting out on a drum’n’bass odyssey of his own.

Dame David’s unlikely mid-Nineties swerve into clattering electronica will be (very tacitly) recognised on Friday 17 April. In acknowledgement of the (now postponed) Record Store Day, Parlophone is putting out ChangesNowBowie, a nine-track live collection originally broadcast by the BBC from 8 January 1997.

Crushingly, nothing from Bowie’s dance phase makes the record. Parlophone has been careful to include only updated renditions of hits such as “The Man Who Sold the World” and “Aladdin Sane”. A cynic might wonder if it’s part of the ongoing campaign to tidy up Bowie’s image. The goal is presumably to ensure only the “classic” material commandeers the spotlight, the awkward experiments and embarrassments quietly written out of history.

What a crying shame that would be. Bowie was outstanding as a tall-haired rock’n’roll extraterrestrial. But he was human, too – and never more engaging than when making a bit of a prat of himself.

Still, revisionism goes only so far. One of the numbers featured on ChangesNowBowie is a cover of The Velvet Underground’s “White Light/White Heat”. The tune was a mainstay of the tour Bowie took around the world in 1997. It was also a hard-rocking aberration in a set that found space for vast chunks of space-jazz noodling.

Typical of this new direction was Bowie’s banging reworking of the old Heroes obscurity “V-2 Schneider”. Its shiny new Nineties incarnation found the star jauntily parping his saxophone as break-beats went batty in the background. Bowie, who hated pandering to his fanbase’s craving for nostalgia, was clearly having a hoot blasting away. With eyes closed as he tooted, he may not have noticed that at least a third of the audience were usually taking the moment to nip to the loo.

Bowie also played lots from the album that he had released in February of that year. Earthling, among its other memorable attributes, featured a striking cover image of Bowie, his hair a Ziggy Stardust shade of red, looking out over a bucolic British landscape.

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

Enjoy unlimited access to 70 million ad-free songs and podcasts with Amazon Music

Sign up now for a 30-day free trial

His back was to the viewer, the better to show off the distressed Union Jack trench coat Alexander McQueen had designed for Bowie’s 1996 co-headline trek across the US with Nine Inch Nails. With the jacket and the green and pleasant vistas, it was almost as if Bowie – a fan of both Blur and Oasis – fancied having a go at Britpop.

Yet the music within could not have been further removed from the Benny Hill pop of Blur or the melodic sludge Oasis were churning out. Bowie had got into The Prodigy while touring his previous record Outside (stylised as 1.Outside) in America.

And that had led him down the rabbit hole into drum’n’bass. The Metalheadz night at the Blue Note popped up on his radar. He was also spending time in Dublin – he would put together the Earthling tour at the Factory rehearsal space in the city’s then dystopian docklands – and became immersed in the drum’n’bass scene there, too. Ziggy was ready to get jiggy with this clattering new twist on dance.

“We’re sitting on the steps outside and he’s rolling a cigarette, loving the place — ‘You’ve got a great set of people in there’ — feeling the influence,” Goldie would recall of his first meeting with Bowie at the Blue Note in his 2017 autobiography All Things Remembered.

“That’s definitely where the energy came from for his drum’n’bass reinvention with the album Earthling. That’s what he was the master of — reinventing himself — but you always knew it was him.”

Goldie would briefly gain entry to Bowie’s inner circle. In his memoir, he recalls his amazement at Bowie agreeing to provide vocals on “Truth”, the best track on Goldie’s notoriously unhinged 1998 LP Saturnz Return (the opening number clocks in at a cortex-numbing 60 minutes).

For Bowie, though, drum’n’bass made absolute sense. Nineties dance music reminded him of the krautrock and early electronica with which he’d become obsessed living in Berlin with Iggy Pop. “V-2 Schneider” had been written in the shadow of the Berlin Wall in 1977 as a tribute to Kraftwerk’s Florian Schneider. That same year Kraftwerk had returned the compliment by taking inspiration from Bowie’s Station to Station with their own Trans-Europe Express.

Thus the idea that Bowie was gatecrashing dance music – a popular view in the Nineties – was unfair and inaccurate. And even if he had been hopping on a bandwagon, it was just the latest of many to which he had hitched himself.

David Bowie: A life in albums

Show all 27Bowie had in 1980 shone a light on the New Romantic movement with “Ashes to Ashes”, the mascara-caked video to which saw the singer dressed as an avant-garde clown. He was joined in that promo by scenesters from the legendary Blitz club in Covent Garden, including Visage’s Steve Strange. Seeking out the cool new underground uprising was just Bowie being Bowie. He was, after a fashion, always crashing the same party.

Besides, it wasn’t as if the Metalheadz night was all that obscure. Goldie had already played Glastonbury; his Hoxton club was attracting a steady parade of celebs, among them Noel Gallagher, Kate Moss and noted pop chameleon Mel B of the Spice Girls.

“Little Wonder”, an early single from Earthling, was perhaps the most successful example of Bowie at the cutting edge. The track flowed from a long-standing ambition to write a song name-checking each of Snow White’s seven dwarfs. This is useful to know if you haven’t previously encountered “Little Wonder” and are puzzled why the composer of “Heroes”, “Ashes to Ashes” and “Starman” is crooning “Stinky weather, fat, shaky hands/ Dopey morning doc, grumpy gnomes.”

Still, things improve immensely as a great wobbling groove kicks in. At the time, Bowie was keen to stress that he was drawing inspiration from drum’n’bass rather than actually working in the genre. That said, he did follow the trend of using samples to build beats. In the case of “Little Wonder”, the drum break was from “Amen Brother” by The Winstons – widely recycled in drum’n’bass – while a spoken word segment had its origins in a Steely Dan live album.

“Little Wonder” charted at 14. Earthling did respectably too, going in at six in the UK album charts and 39 in the US. Among Bowie aficionados, the reception was mixed, however. Dylan Jones, in his 2018 Bowie rumination David Bowie: The Oral History, recalls the singer inviting him to a personal playback of the record and turning slightly haughty when Jones didn’t share in his enthusiasm.

“Stereogum rated it as his 17th best album,” Jones wrote. “I think they’re being kind.”

Some might think that Jones is being too dismissive. Today, rock stars are allowed go on being rock stars until they drop. In 1997, 50 was regarded as the final frontier for Bowie and his generation.

The idea that someone who had been putting out LPs for nearly three decades would still aspire to forging ahead creatively was regarded as absurd and slightly embarrassing. Especially at a time when younger artists – Blur and Oasis in particular – were unashamedly picking the pockets of pop’s past.

“Growing old in this business is a really fascinating prospect because it’s never been done before,” Bowie told Jones. “I’ve still got an insatiable appetite and either you’ve got to voice that excitement through your work or give up. I’m not going to spend the rest of my life bashing out those songs which make you remember when you first met your wife.”

Bowie had a point. And besides, whatever Jones and Stereogum thought, there are some cracking moments on Earthling. “I’m Afraid of Americans”, originally debuted on the soundtrack to Paul Verhoeven’s Showgirls and, co-written with Brian Eno, was a rollicking rant against US cultural imperialism. Among other pleasures, it featured industrial riffs from Bowie’s 39-year-old guitarist Reeves Gabrels and one of Bowie’s catchiest choruses since the Seventies.

Also worth investigating was apocalyptic ballad “Telling Lies”, where Bowie had a go at sounding like Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor fronting Depeche Mode. “Seven Years in Tibet”, meanwhile, unfolded like a breathless goth-electronica assault. And “Battle for Britain (The Letter)” was a top-drawer Bowie ballad with glow sticks – Hunky Dory’s “The Bewlay Brothers” on a lost weekend in Ibiza.

Alas, Bowie’s canonisation as unimpeachable rock icon was still a few years away. In 1997, he continued to have a crosshair on his back. The Eighties weren’t all that distant: perceptions of Bowie as Phil Collins with a quiff hadn’t quite dissipated (though they soon would). All of which may explain why Earthling received a critical pummelling. Particularly scathing was the one-star write up in then-influential Select magazine.

“After 30-odd years of preening and variable reinvention, he’s arrived at his strangest one yet: middle-aged arena drum’n’bass fantasist,” it went. “Earthling is splendidly coiffured and presented, just like the old boy himself. But the selling-point – Bowie goes original junglist nuttah – is so negligible as to be non-existent. And what remains is not good.”

He was an easy target, then. Even today, Earthling does not always receive the credit it deserves among Bowie fans. Along with its 1995 cyber-noir predecessor Outside, there’s a case that it represents the most unheralded phase of his career. Still, those that liked it were steadfast in their enthusiasm.

“I really liked Earthling,” The Cure’s Robert Smith would later say. “I thought it was a really good album. The songs are great songs. They really stand up to be listened to AS songs and the fact that he worked in a particular genre and tried to capture a certain sound is neither here nor there. The songs are really well put together.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies